By Sophie Quinto

Community colleges charge lower tuition than just about anywhere else. They’re open to everyone. They offer the kind of technical training employers want. And they can serve as an affordable steppingstone to a four-year degree.

As President Barack Obama said in the fall: “They’re at the heart of the American Dream.”

But while plenty of community college students graduate with a degree that leads to a better job, or to a four-year college, many community college students drop out. And a growing number of students are taking on debt they cannot repay.

States have focused more on reducing the debt students accumulate at four-year colleges than at community colleges. But some of the steps they’re taking could help community college students, as well.

Most states are now partly funding public colleges and universities based on whether students graduate on time. And some states are tackling community college costs by creating scholarships that eliminate tuition, as Obama has proposed.

In 2000, 15 percent of all first-time college students seeking degrees at a public two-year college borrowed. Twelve years later, 27 percent did. At Michigan’s Macomb Community College, where Obama spoke, just 6 percent of students take out federal loans. But of those students, who typically owe $5,170 at graduation, 18 percent default on their loans.

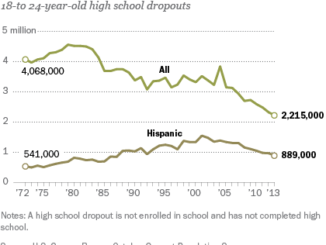

Working-class people poured into state community colleges and expensive for-profit trade schools when the economy soured. Although for-profit colleges tend to charge higher tuition, research shows that in recent years typical for-profit and two-year college borrowers have similarly high default rates.

Thirty-eight percent of two-year college students who started to repay their loans in 2009 defaulted within five years, as did 47 percent of for-profit college students, said a September study led by Adam Looney, an economist at the Treasury Department. Just 10 percent of students who attended selective four-year colleges defaulted over the same period. The vast majority of two-year colleges are community colleges, the study noted.

Default rates are now falling, along with enrollment at community and for-profit colleges. But Looney’s study warns that many borrowers who attend the institutions will continue to struggle in the student loan market.

Not Just a Four-Year Problem

Many community college students start out with the odds against them. They tend to be older, live in poorer communities and have little family wealth to support them — 36 percent have family incomes of under $20,000, according to the Community College Research Center at Columbia University.

Still, community college students historically haven’t had to borrow to finance their education. Tuition usually runs a few thousand dollars a year — from $1,400 in California to $7,500 in Vermont. Low-income students who qualify for the maximum federal Pell Grant — $5,815 this year — usually find that their grant covers tuition.

Yet increasingly, community college students are borrowing. In Virginia, one of the few states to publish detailed student debt information, the share of community college students graduating with debt has more than doubled over the past decade.

In 2014-15, when community college tuition was $4,080, 37 percent of Virginia graduates who earned a two-year degree that prepared them to transfer to a four-year college had debt, up from 15 percent a decade ago. Among graduates who earned a two-year occupational degree, 41 percent had debt.

(Virginia’s community college system says the state debt figures are too high, but that may be because the state is calculating debt differently. The state looks at debt owed at the point of graduation, which may include debt from other institutions.)

“They’re borrowing for things just beyond the cost of tuition and fees. They’re borrowing to live,” said Tod Massa, who oversees the state’s postsecondary education data.

Many community college students need to borrow to pay for textbooks, transportation, food and rent, even if they’re working while they go to school. The total cost of attending a Virginia community college rose from $9,410 a year to $15,083 over the past decade for full-time students who live with their parents, according to state data. Students who live on their own pay more.

More Virginia community colleges include federal student loans in financial aid packages now than in past years, which also could be pushing up student debt.

Small Loans, High Default Rates

Policymakers tend to focus on stories of scary-high debt, such as a graduate student who owes six figures. But students who owe much less are more likely to default.

“The typical loan in default is around $5,000. That’s total, that’s not per year, that’s all that someone borrowed,” said Susan Dynarski, a University of Michigan professor of public policy, education and economics.

At Old Dominion University in southeast Virginia, for example, the average graduate with federal debt leaves school owing $23,900, according to federal statistics. Seven percent of graduates default on their federal loans within three years. But at nearby Tidewater Community College, where the average graduate with debt leaves owing $10,250, twice as many graduates default.

Student loans can create a snowballing crisis for borrowers. Debt that cannot be repaid can lead to default, fees from loan servicers, a damaged credit score, and eventually the garnishment of wages or government benefits. In some states, people can lose their professional licenses or driver’s licenses as a result of defaulted student loans.

A lot of factors determine someone’s ability to repay their loans, including what kind of job they’re able to get after graduation — which can depend on their major and the local economy — and whether they graduate at all.

The small size of loans in default suggests that many borrowers dropped out, Dynarski said. And students who drop out don’t get to enjoy the financial payoff of a higher credential.

At colleges that serve more lower-income, minority and first-generation students, such as community colleges, graduation rates are typically lower. About 38 percent of students who entered public two-year colleges in 2009 graduated, or transferred and completed a four-year degree, compared to 61 percent of students who started at a four-year college, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

Completion, Affordability and Managing Debt

States are taking a few steps to hold down college costs and put pressure on all colleges to make sure students graduate. As of fiscal 2015, 26 states were spending part of their education funding to reward outcomes such as graduation rates. And 10 more were moving in that direction, according to HCM Strategists, a consulting firm.

Many states, including Virginia, increased funding for all higher education institutions this year and asked colleges to hold down tuition. Tennessee, Oregon and Minnesota have created scholarship programs that make two-year colleges tuition-free for students who meet certain requirements.

Some researchers and advocates say tuition-free programs don’t go far enough because paying for living expenses — not tuition — is the biggest financial problem most community college students have.

To tackle that, Sara Goldrick-Rab, a professor of educational policy studies and sociology at the University of Wisconsin, said states could increase grant aid or follow Minnesota’s example and extend work-study opportunities.

States also have started to take some steps to help borrowers who are struggling with existing student loan debt.

Virginia state Del. Marcus Simon, a Democrat, said his colleagues in the Legislature have long considered student debt to be a federal issue. But he thinks the state can help. This year, he put forward bills that would allow students to refinance their loans through a state authority, require student loan servicers to get a license and create an office to inform and assist borrowers.

“We want to create a system where there’s some regulation, there’s some oversight, and there’s just some basic information that you have to get about your loan,” Simon said.

Refinancing likely wouldn’t be an option for borrowers who are behind on their loans, or have damaged credit. But all borrowers could benefit from more information and assistance.

Some borrowers don’t know the difference between a grant and a loan, let alone that some federal programs will reduce their monthly payments to nothing while their incomes are low. The fact that people with low earnings are defaulting shows that not enough of them have enrolled in those programs, Dynarski of the University of Michigan said.

Last year, Indiana began requiring all institutions that enroll students who receive state financial aid to provide students with an annual estimate of their total loan debt and future monthly repayments. A new Nebraska law requires all publicly funded postsecondary educational institutions in the state to provide that information to students.

Colleges, which are penalized by the federal government for high default rates, are trying to help students graduate and keep them from falling behind on payments.

To keep students on the path to graduation, Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA), the largest two-year college in Virginia, has redesigned remedial math classes and hired counselors to work with freshmen to help them find a major and schedule courses. The school also has contracted with a company that sends delinquent borrowers automated phone calls and another that counsels them over the phone.

Some colleges warn students not to take out too much money for living expenses, and some will deny loans.

“We see a significant number of students who are coming to us with existing loan debt,” said Joan Zanders, head of financial aid and support services at NOVA. If a borrower owes $70,000 from prior education, say at a for-profit college, “it makes no sense whatsoever for them to dig a deeper hole for themselves to get a certificate.”

NOVA officials say there’s a link between financial education and academic success. When students can budget their financial aid money and pay their bills, they’re more likely to stay in school. So NOVA’s required orientation course now includes a unit on how to stick to a budget, manage credit cards and understand student loans.

Like community colleges across Virginia, NOVA saw a spike in borrowing during the recession. Now, Zanders said, “it’s actually going down.” She said she thinks this is partly due to the improving economy and partly due to better outreach.

Sophie Quinton writes about fiscal and economic policy for Stateline. Previously, she wrote for National Journal, where she covered the White House and was a lead reporter for series on demographic change and the economy.