by Jenna Johnson, Washington Post

During the Medina County Fair parade on Saturday morning, John Resendez and his relatives sat in camping chairs across the street from an early voting center.

Beauty pageant winners waved, sirens blared, children blew bubbles and a float bearing Confederate flags trundled by, along with an SUV decorated with campaign signs for Republicans and a trailer plastered with banners for Democrats. Monarch butterflies flitted along the route.

A woman wearing a T-shirt promoting Beto O’Rourke, the Democrat running for U.S. Senate, handed out fliers with polling location information and told the children sitting on the curb in front of Resendez: “You get all of these people out to vote, okay?”

Resendez, 34, laughed and said, “Tell her you shouldn’t be doing her job!”

Amid the laughter came a sober reality, particularly for Democrats trying to reverse the Republican hold on Texas: That back-and-forth was Resendez’s first interaction with a campaign this year — and it came just 10 days before the election, and after the deadline to register to vote.

Resendez would not have needed much convincing: He is dismayed by President Trump’s treatment of Latinos and wanted to cast his first-ever vote.

“It’s already too late, isn’t it? That’s too bad. I guess I just postponed it too much,” said Resendez, the father of a 6-year-old son who lives in this small town, about 40 miles west of San Antonio, where he works as a loop technician and tattoo artist. “I need to start putting an interest into it.”

This year, the country’s growing Latino population could again play a deciding role in races in Texas and elsewhere — and, once again, Latino activists say that Democratic and Republican campaigns have neglected to spend enough time and money directly encouraging Latinos to register and vote.

Latinos have long voted at lower rates than whites and African Americans. Only 45 percent of Latinos who are eligible to vote turned out in 2016, compared to 65 percent of whites and 60 percent of blacks. The rate was even lower during the two previous elections: 21 percent of Latinos voted in 2014, and 43 percent did so in 2012.

To increase those percentages, activists say campaigns need to do more than run ads in Spanish or host rallies in towns with large Latino populations — they need to hire field staffers who can build relationships in Latino communities, canvass homes beyond those of already-registered voters and guide new voters through the sometimes daunting registration and voting process.

Questions surrounding that process clearly exist: When Univision began to promote a nonpartisan, bilingual national hotline for Latino voters last week, more than 40 percent of calls on the first day came from Texas.

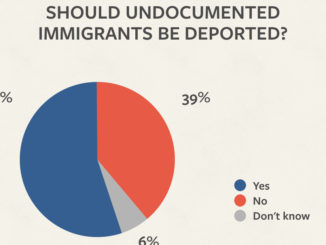

Some Latinos are reluctant to become politically involved. In the immigrant community, some fear that showing up to a polling location, especially those located in government buildings, could draw attention to unpaid traffic tickets or relatives who are in the country illegally. And then there’s the apathy that plagues all voters.

Texas makes registration difficult: There’s no way to register online and the state requires those who register potential voters to be certified in the county where the registrants live — making it difficult to register people at events that draw Texans from numerous counties.

Recruiting Latino voters should be made easier for Democrats by Trump, who has cast undocumented immigrants as dangerous criminals who “infest our country,” overseen the separation of migrant children from their parents at the border and closed out his midterm pitch by calling for an end to birthright citizenship, by which babies born in the United States are made citizens regardless of their parents’ legal status.

“Latinos will vote when they’re angry or there’s hope. This election is bringing both,” said Lupe Valdez, Texas’s Democratic gubernatorial candidate, the former Dallas County sheriff who is the daughter of Mexican migrant workers.

A recent study by the nonpartisan Pew Research Center found that 52 percent of Hispanic voters say they have given “quite a lot” of thought to 2018 midterm elections — less than the 67 percent who said the same in 2016, or the 61 percent in 2012, but higher than the percentages during the 2014 and 2010 midterms.

“Motivation is very high right now — so it’s not that folks aren’t interested in becoming more engaged,” said Blanca Flor Guillén-Woods of Latino Decisions, a polling and research firm. “It takes more than motivation. It actually does require some assistance to get those folks to the polls. … After they’ve voted a few times, they’ve got it, they become voters, they become consistent voters.”

Of the 73 congressional races that have been deemed most competitive by the Cook Political Report, 25 are in districts where Latinos make up at least 10 percent of eligible voters. In 12 of those districts, Latinos make up at least 20 percent of eligible voters, according to Pew. Latino voters could play a major role in the Senate and governor’s races in Florida and Nevada, the governor’s races in Colorado, Connecticut and New Mexico, and the Senate races in New Jersey, Arizona and Texas.

Here in Texas’s 23rd Congressional District — which stretches from El Paso to San Antonio and includes 820 miles of the southern border — nearly 65 percent of eligible voters are Latino, according to Pew. The district backed Democrat Hillary Clinton in 2016 and is represented by Republican Rep. Will Hurd, a former CIA operative who is black and won his last election by 3,000 votes. His Democratic opponent is Gina Ortiz Jones, a former Air Force intelligence officer. Neither candidate speaks fluent Spanish.

Republicans have accused Jones of “pandering for votes in Texas” by using her middle name, which sounds Hispanic but is her Filipina mother’s last name. On the campaign trail, Jones often talks about the sacrifices her mother faced immigrating to the United States and raising two daughters as a single parent while working several jobs. Jones cut short her military career when her mother was diagnosed with cancer in 2006.

“Ninety-five percent of people in this community would do the exact same thing,” Jones said over coffee at a San Antonio taqueria. “That’s something that resonates with the Hispanic community.”

Notably, however, Jones went largely unrecognized in the taqueria.

Jones said she has focused on reaching already-registered voters and left finding new voters to “a patchwork effort” by nonprofits and grass-roots organizations. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, which supports House candidates, has had organizers in the district since February 2017, and hopes to interact with “Democratic base voters” at least 100 times each in the 60 days before the election. Texas Democrats are excited that more than 400,000 Texans have registered to vote since March, and many counties have seen record turnout for early voting.

Republicans in Texas are also competing for Latino votes. Gov. Greg Abbott (R) won 44 percent of the Hispanic vote in 2014 and is determined to increase that percentage this year. He has had an active campaign since 2014 and believes that many nonvoters are conservatives, not liberals.

“Texas Hispanics, as a bloc, are different than Hispanics in California or New Jersey or parts of Florida. They’ve been here before Anglos were here. They’ve been here for generations,” said Dave Carney, a consultant on Abbott’s campaign. “Texas is culturally and intellectually and ideologically a right-of-center state.”

Hovering over all Texas races is O’Rourke, who has raised more than $70 million and sparked a grass-roots movement that has received national attention. O’Rourke declined to endorse Jones because he has a bipartisan friendship with Hurd, frustrating party leaders.

O’Rourke has invested heavily in digital advertising — and some Texas activists say he has not spent nearly enough on a get-out-the-vote operation, instead relying heavily on volunteers. The campaign, which recently added more paid field staff, did not respond to several requests for comment.

“I think that Beto got the message. I think now they’re knocking on enough doors, but I’m a little concerned that they started to do it as late as they did,” said Cristina Tzintzún, the executive director of Jolt, which aims to engage young minority voters. “It’s a big state to cover, and I wish that there would have been more investment early on in the Latino community and voter registration work.”

Ahead of the Medina County Fair parade, nearly every table was filled at Taqueria El Rodeo De Jalisco, which is just down the highway from Hondo’s welcome sign that reads: “This is God’s country. Please don’t drive through it like hell.”

Medina County is home to 50,000 Texans, 52 percent of whom are Hispanic. Trump won the county with 70 percent of votes, and Medina was pivotal in a special election earlier this year in which Republicans won a state Senate seat long held by Democrats.

Chris Malandas, a 26-year-old manager at the taqueria, said that he registered to vote for the first time because he was inspired by O’Rourke’s campaign. His customers included several Democrats who had already voted, a 73-year-old truck driver and longtime Democrat who is tired of watching party leaders “stand around and wait for the other side to make a mistake,” and a high school freshman who said he has been bothered by the ads he hears on Spotify attacking Hurd, who has visited his school.

Briana Perez, a 28-year-old sales associate, said she has never voted but wants to start — she did not realize she had missed the registration deadline. No campaign has reached out to her, she said.

“Things just got past me, I guess,” said Perez, who has a newborn baby. “I know it’s important. I know it’s important.”