by Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux, FiveThirtyEight

On Friday, a federal appeals court handed down another setback for President Trump’s effort to crack down on sanctuary cities, a campaign pledge that he has been fighting to fulfill since his first few days in office. The judges in the case ruled that the Trump administration could not withhold federal law-enforcement funds from cities that limit their cooperation with federal immigration agents. The ruling came down on the same day that Trump declared a national emergency to secure funding to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border — another effort to fulfill a key campaign promise, and one that will almost certainly be mired in a lengthy legal process where a win is far from guaranteed.

Why is the president so willing to dig in and risk legal defeat when it comes to his signature immigration issues? It might be because without cooperation from Congress, Trump’s best shot at fulfilling some of his key campaign promises is to take bold — and possibly unconstitutional — actions and hope for a victory in the courts. Even a series of losses might seem better, from a political perspective, than doing nothing. As Christopher Lasch, a law professor at the University of Denver, told me, “To the extent that he can tell his base he’s trying to do something, that’s a win for Trump — regardless of how the cases turn out.” In the case of sanctuary cities, what’s at stake is the balance of power between the federal government and state and local authorities — and so far, judges have almost uniformly sided against the federal government.

From the beginning, Trump and his administration have been fighting an uphill battle against sanctuary cities. Judges across the country — appointed by both Republicans and Democrats — have rejected several attempts by the administration to yank federal funding from cities that limit cooperation with federal immigration-enforcement efforts, and a federal judge in California refused the administration’s request to suspend the state’s sanctuary laws. “They’ve been roundly defeated again and again,” said Ilya Somin, a law professor at George Mason University.

Many of these cases revolve around a federal law that says cities and states can’t forbid their employees from communicating with federal agents about the immigration status of people in their jurisdiction. An executive order issued by Trump in his first few days in office and the conditions later placed by former Attorney General Jeff Sessions on law-enforcement grants both make federal funding at least partially contingent on compliance with federal agents.1 But legal experts told me that it’s unconstitutional for a president to try to attach these kinds of strings to funding, because Congress controls spending and therefore only Congress has the power to impose conditions on federal grants. The law itself may also be unconstitutional under the 10th Amendment, which shields states’ rights. Several judges have made this point in their rulings, relying on a 2018 Supreme Court decision that was authored by conservative Justice Samuel Alito and overturned a federal sports gambling law on the grounds that it was “commandeering” the states to enforce federal laws.

These recent lower-court rulings may have been predictable — at least to legal experts. But the Trump administration pressed on anyway, perhaps because the success of Trump’s immigration agenda partially depends on his ability to get local law enforcement to work with federal agents. It’s hard for Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents to locate undocumented immigrants without the help of state or local police.

“It’s more cost effective and efficient for ICE to pick people up who’ve already been arrested and held in the local jail than to go find them in their home or elsewhere,” said Randy Capps, director of research for U.S. programs at the Migration Policy Institute. According to a 2018 report from his organization, 69 percent of ICE arrests during the first 135 days of the Trump administration were based on transfers from the criminal-justice system. The institute also found that California’s share of overall ICE arrests fell after statewide sanctuary policies were implemented, while the share of arrests rose in some other parts of the country.

Given this context, it makes sense that the Trump administration would continue to fight sanctuary cities, despite the administration’s string of defeats so far. And Trump may be banking on a more favorable hearing at the Supreme Court, which ultimately upheld his ban on travel to the U.S. from a number of countries, including several where the majority of the population is Muslim, after a series of losses in the lower courts. Most of the legal experts I spoke with were skeptical, though, that the justices would be willing to take the cases involving conditions on federal grants unless the administration wins in at least one appellate court.2

But if the goal is to demonstrate to Trump’s base that he’s working to fulfill a key campaign promise, his record in the courts may not really matter. Jessica Vaughan, the director of policy studies at the Center for Immigration Studies, which seeks to decrease immigration to the U.S., said that Trump faces significant pressure from his base to do something — anything — to fight back against sanctuary cities, which is why it could be more politically costly to back down than to continue losing. “The people who support increased immigration enforcement are very frustrated with this status quo, and they want to see the Trump administration take it as far as possible,” she said.

And the president may simply feel that he doesn’t have much to lose by continuing to fight. Taking a few more defeats on sanctuary cities won’t change much right away, since the administration is already losing across the board. It’s possible that if California’s sanctuary law is ultimately upheld, more states will decide to pass similar legislation, but that process would take time. And by tying state and local governments up in expensive legal battles, the administration could end up deterring some smaller or less firmly Democratic cities from enacting sanctuary policies, Lasch said.

“Even if he keeps losing, that reinforces the narrative that the Trump administration is trying to enforce the nation’s immigration laws and the courts are against them,” said Ilya Shapiro, director of the Center for Constitutional Studies at the right-leaning Cato Institute. Trump could be making a similar calculation about declaring a national emergency: Settling in for a series of defeats in the short term could turn out to be a successful political strategy in the long run.

Other cases

Pre-presidency Trump

- A federal judge ruled that former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort intentionally lied to special counsel Robert Mueller’s team, in violation of his plea agreement. As a result, Manafort’s plea deal is no longer in effect, which means he could spend the rest of his life in prison.

- Former Trump adviser Roger Stone is now under a limited gag order issued by the same judge after Stone went on a media blitz last month discussing his indictment and arrest as part of Mueller’s investigation. Then Stone posted a picture to Instagram that included a picture of the judge’s face with crosshairs in the background, prompting the judge to schedule a hearing for Thursday to discuss the conditions of his release. Stone apologized to the judge and took the image down, but she indicated that his release on bail could now be in jeopardy.

President Trump

- Last spring, a judge ruled that Trump violated the First Amendment when he blocked people from viewing or replying to his posts on Twitter. Trump appealed the case to the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, where oral arguments were recently scheduled for March 26.

The Trump administration

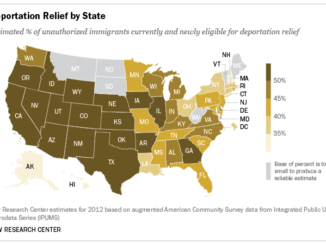

- On Friday, another case involving Trump’s decision to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program — which removes the threat of deportation from certain undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children — will be argued before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Last spring in the same case, a federal District Court judge ruled that Trump’s reasons for revoking the program were “virtually unexplained” and the revocation was therefore illegal.

- William Barr was confirmed as attorney general on Thursday, triggering the dismissal of several challenges to acting Attorney General Matthew Whitaker’s appointment last November.

- Last Friday, Trump declared the situation on the country’s southern border to be a national emergency in order to secure funds to build a long-promised wall between the U.S. and Mexico. On Monday, the attorneys general of 16 states sued the president, arguing that his declaration violates the Constitution’s separation of powers. Another lawsuit has been filed against the president by an environmental organization and several landowners in south Texas who say they’ll be affected by the construction of the wall, in addition to a separate lawsuit filed by several environmental and animal rights groups. A watchdog group is also suing the Department of Justice for failing to provide records related to the president’s legal authority to invoke a national emergency. All of these cases have been added to the latest update of the Trump Docket data set.

This is the Trump Docket, where we track some of the most important legal cases of the Trump presidency and how their results could shape presidential power. Questions, comments, or thoughts about cases to cover? Email us here.