by Julio Ortega

Book: El Norte: The Epic and Forgotten Story of Hispanic North America

By Carrie Gibson

One hundred years before the arrival of the Pilgrims, Mexicans were already here. (With typical dark humor they used to say that when God ordered Fiat lux!, Hispanics were late with the bill for the electric company.) Carlos Fuentes was 10 years old when his father, a Mexican diplomat in Washington, took him to see a film that included the secession of Texas from Mexico; the boy stood up in the dark and cried, “Viva Mexico!” It was a sense of duty he carried all his life. Gabriel García Márquez journeyed to the South, following in Faulkner’s footsteps. In his own Faulknerian accounts of too many years of solitude he adds that the Americans, with the excuse of eradicating yellow fever, stayed in the Caribbean far too long. Fuentes was once forbidden to disembark from a ship in Puerto Rico, and García Márquez was asked to strip naked at customs.

“El Norte: The Epic and Forgotten Story of Hispanic North America” is the book that Americans, Anglo and Hispanic, should read as an education on their own American place or role. The author of “Empire’s Crossroads: A History of the Caribbean From Columbus to the Present Day,” Carrie Gibson takes on the task of accounting for the relevant and telling cases of our modern process of national formation and regional negotiations. This is a serious book of history but also an engaging project of reading the future in the past.

Crossing borders has become a formal rite de passage toward identity, and Latin Americans are experts in dealing with the walls, fences and barriers of misreading — as Mexican, Hispanic-American, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Caribbean and Latin American, not to mention Latino, mestizo, mulatto, Native and every other wall of misrepresentation. This formidable display of categorization has produced a complex and intricate cultural system of representing ethnic territories, racial mappings and exclusionary perceptions. To split the atom has proved to be easier than to split a prejudice. The civil society reinforced what is not-inclusive: skin color, religion and language. Identity was forged from the color of the others, languages of origin, religions and bone size.

Gibson recounts this forgotten epic, but one can also read her story as a reliable travel guide, a long ride along the path of an elusive but powerful history. And even if that history is new to most of us, it is a familiar tale for many nations moving beyond the walls into a territory of common goals. In most of the cities there have been people writing and protesting, forging from modest presses a regional demand for a possible public space, voices of a civilization and of a law against intolerance and violence. They are the forgotten heroes of the press, journalists and chroniclers, travelers and booksellers.

Some of the cases in “El Norte” are more tragic than others, like the painful history of Puerto Rico, where the Arawak people, or Tainos, the pacific society that Columbus encountered, had an easy laugh and were as curious as children. We now know, thanks to the Spanish historian Consuelo Varela, that Columbus stopped their baptism as Christians in order to sell them as slaves; he even managed to get a percentage from the first bordello in the Americas. The Tainos, of course, disappeared, but others in the Caribbean did not. They didn’t appreciate Columbus’s gifts of marbles, and they would have returned to Donald Trump the paper towels he threw to the victims of Hurricane Maria. History repeats itself, now as shame.

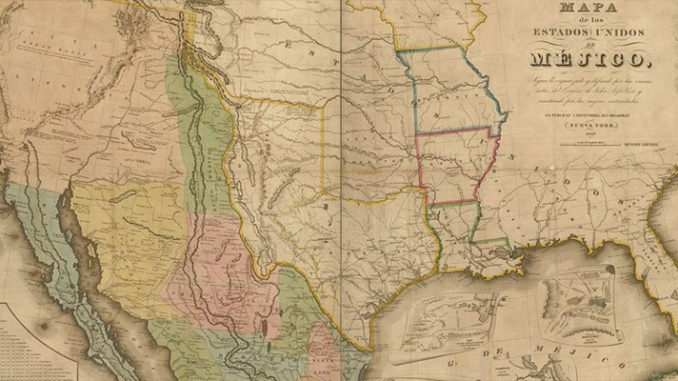

What is particularly fascinating about this book is that its encyclopedic project is not a rewriting of history but a recitation of readings. Almost each historical event is retold through memory, recording, evaluation and discussion. This is history as dialogue. It leaves the mourning authority of archives and takes its place as a long conversation, presupposing that truth can be reached through an extended pilgrimage, a journey through violence, discrimination, racism, exploitation and the inferno created by occupation. The narrative becomes not a tribunal but a hospice to language, shelter to the loss of meaning imposed by violence. Mexico lost half its territory and many lives, but the voices of Thoreau and Lincoln are here to sound an alarm and to hope. The model of replacing a tribunal with a conversation is reminiscent of Montaigne: Lacking friends, he lamented that Plato was not around to talk about the wonders of the New World and its inhabitants, who ignored the distinction between “mine” and “yours.”

Gibson lets the facts speak. But one would also like to read the saga of memory, that is, the version of the epic of “El Norte” through literature and fiction. The writer and critic Domingo F. Sarmiento came to the United States to learn from the American example of progress, and as president of Argentina to replicate those monuments of civilization that he saw: schools, railroads, immigration. Each of them fell short of his expectations. The Cuban poet and activist José Martí loved New York, but found that the people were composed of the “yeast of tigers.” In “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” García Márquez retells the American arrival in the South through the town of Macondo — where they discover the banana, move the river, bring modern tools. But it all ends in a massacre. Fuentes relates the story of an old writer who moves to Mexico: “A gringo in Mexico, that is euthanasia.” Roberto Bolaño recounts the number of women killed around the maquiladoras. The border but also the migration, narcotics but also life in-between are elaborated in Yuri Herrera’s fiction. The displacement of women in the novels of Carmen Bullosa and Cristina Rivera Garza, as well as the chronicles of Heriberto Yépez on dying-daily in Tijuana, explore new discourses of sorrow.

The North has also become a growing space of rereading. The Mexican-American novelist Rolando Hinojosa-Smith used to say that as a kid from El Valle, he started reading fiction that had been translated into Spanish. He thought that all writers were Mexicans, despite some strange names — Dumas, Chekhov, Dos Passos. It seems that el Norte is not only a cemetery. It is also a national library.