by Taylor Swaak

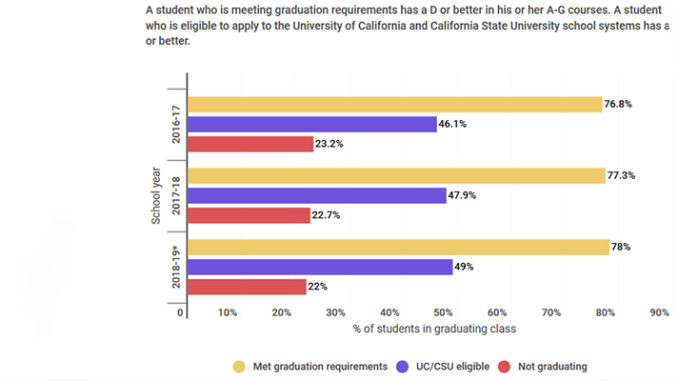

Less than half of the class of 2019 in Los Angles are eligible for the state’s public universities, the latest school district projections show.

As of March, 49 percent of L.A. Unified’s 34,734 prospective graduates are on track to pass all of their “A-G” college preparation courses with Cs or better. This means that less than half of the class currently have the grades to qualify for the University of California and California State University school systems. These in-state schools are a popular option for graduates, especially as about 4 in 5 L.A. Unified students are minorities from low-income families — some first-time college-goers.

“I have very high expectations for where the district and where our students should go … so no, [these rates] don’t meet my expectations for what our kids are capable of,” said board vice president Nick Melvoin, who amended last year’s “Close the Gap by 2023” resolution to require the district to start reporting students’ eligibility for state colleges in addition to the standard graduation rate.

There are 15 A-G courses in all district high schools, including English, math, science, foreign language and other core electives. Students need to get Ds or better in those courses to graduate, and Cs or better to be eligible for the US/CSU systems. L.A. Unified’s class of 2016 was the first cohort that had to complete all of those courses in order to earn a high school diploma.

The percentage of students meeting the state’s public university requirements has only slightly ticked up since then. About 46.1 percent of the class of 2017 and 47.9 percent of the class of 2018 got Cs or better. These data account for all prospective graduates in a given year — not just those who graduated — and include the district’s affiliated charter schools but not independent charters.

The class of 2019 projections also reflect a continuing trend: a nearly 30-point difference in who meets graduation requirements versus those who meet state college eligibility standards. About 78 percent of that class’s students are on track to graduate with Ds or better, but only 49 percent are anticipating Cs or better. That means 29 percent could receive a diploma come June while simultaneously failing to qualify for UC and CSU schools. (Not to mention the 22 percent who currently aren’t on track to graduate.)

When only graduates are factored in, the percentage of those who got at least a C is notably higher: 60 percent in 2016-17 and 61.9 percent in 2017-18. This is because the students with the lowest grades — those who didn’t graduate — are not included in the count.

To confront the low rates, the district set a goal last year that 100 percent of high school graduates would be eligible to apply to a California four-year university by 2023. On top of offering credit recovery opportunities — there’s a session running from March to May, including spring break this week, that’s open to students who have failed a class — L.A. Unified is also expanding its data transparency and access districtwide to college tests like the SAT. But early intervention efforts, parent engagement and staff’s own expectations for student achievement continue to lag, advocates say.

“For kids to succeed — in A-G, graduation, all of these pieces — it starts earlier; we have to develop the pipeline, we have to have parents be part of this,” said Yolie Flores, a former school board member who is now chief program officer at the Campaign for Grade-Level Reading. “You can’t turn to another issue, and another issue, and not keep pushing.”

‘Better but unacceptable’

Flores remembers a presentation on A-G courses in 2011 that almost brought her to tears.

It was more than five years since scores of students, parents and community members blasted the district for how their schools — many attended by minority and low-income students — lacked the high expectations and access to A-G courses that more affluent neighborhoods had. An “A-G for All” resolution passed soon after in 2005, laying the groundwork for full districtwide access to these courses starting with the class of 2016.

During one of Flores’s last meetings in office, the school board received a progress update: Only 26 percent of students were on track to meet A-G requirements.

Flores was “devastated.”

“What came to mind was all of the work from the community, all of the advocacy and just blood, sweat and tears that had been spent organizing and finally getting this A-G resolution passed,” she said. “And we had made such little progress. I remember turning to my staff and saying, ‘I don’t think I’ve ever felt like crying in public like I do right now.’”

Looking at more recent data, Flores says the rates are “significantly better. But unacceptable.”

District officials and advocates offered numerous reasons why the percentages are still low. One is the caveat that L.A. Unified students can still graduate if they get Ds in their A-G courses, even though Cs are required for the UC/CSU systems. Graduation, therefore, doesn’t necessarily guarantee a college education or viable career choice.

The initial plan was to require students to pass their A-G courses with a C in order to get a diploma. But the D-or-better standard prevailed under the logic that “it’s not fair to kids to go from one year [having] no A-G courses, and for the next year, ‘If you don’t get a C, you’re not graduating,’” Melvoin said. He added that quickly changing the graduation requirement to passing with Cs would likely force more students into taking make-up courses. In 2015-16 alone, 42 percent of graduates had retaken a class they had failed or needed some other kind of credit recovery to graduate.

And a C in itself still isn’t always enough, as nonprofit organization Innovate Public Schools pointed out in a tweet. “You need to do even more [than getting a passing grade] to be ready for college and to be able to get into a more selective school,” the tweet reads.

So a D requirement effectively “does nothing for kids,” Flores said. “Kids try to get into schools, and they’re so behind.”

Melvoin cited underfunding and “systemic poverty” as other factors. (California’s schools rank 41st in the nation for per-pupil spending.) And he added that L.A. Unified is still playing catch-up after decades of not holding all student groups to the same standards.

Disparities in college preparedness across student groups are stark. For the class of 2018 — not including any charters — 46.3 percent of Latino students, 16.6 percent of foster youth and 21.3 percent of English language learners were eligible for the state’s public universities, according to state data.

Jennifer Cano, who works for United Way of Greater Los Angeles, has heard stories firsthand from students in the organization’s Young Civic Leaders Program. “They have teachers who are champions and teachers who are obstacles,” said Cano, director of education programs and policy. “Some who have even said to them, ‘Well, you’re not going to amount to anything,’ or ‘College is not for you.’ Or counselors [say it].”

Flores also spoke to the damage of low student expectations, which to her trumps the “poverty” argument.

“Yes, we have to fix [poverty] because that makes things harder, but that’s not an excuse,” she said. “We have to stop blaming poverty and zip codes. We have to start with high expectations.”

Moving toward change

L.A. Unified’s progress is moving “not nearly rapidly enough,” Melvoin acknowledges. But he cited increased transparency as one success, now that both sets of grad rates are reported. Last year’s launch of the Open Data Portal, which Melvoin spearheaded, is also getting more data to the public, though there’s still more work to be done to make the data more parent-friendly.

Transparency is important as L.A. Unified vies for new revenues, he said.

“Especially as we’re talking about the parcel tax, we want to make sure that we’re transparent,” Melvoin said. The parcel tax on the June ballot would raise about $500 million annually for L.A. Unified schools, costing $240 a year for an owner of a 1,500-square-foot home, for example.

Access to testing is also expanding. Last month was the first time L.A. Unified paid to have all district juniors take the SAT in school — a reported $1.2 million cost, according to the L.A. Times. This districtwide offering came after Local District South’s 29 high schools piloted a free testing day last year that nearly doubled the percentage of its students who took the test.

All traditional high schools provide opportunities for Advanced Placement courses as well, the district confirmed. But “based on the size of the school and student interest, some schools offer more AP courses than others,” a district spokeswoman wrote in an email.

Here are some other efforts to boost A-G pass rates that are being pursued or suggested:

1 Credit recovery courses.

District students can retake a class they failed during the regular school day. There are also Saturday sessions — offered through the Division of Adult and Career Education — that are running from March through the end of May, as well as every weekday during spring break, the spokeswoman confirmed. About 800 high school students are currently enrolled.

2 Getting to a C graduation requirement over time.

“Not immediately,” Melvoin said, “but in four or five years so that it’s a warning sign to eighth- and ninth-graders that ‘Hey, you’re going to need to do this in order to graduate.’”

His office confirmed that there are no related resolutions scheduled at this time.

3 Replicating good practices of other schools.

About 87 percent of 2018 graduates attending 72 independent charters earned Cs or better in their A-G courses — a rate more than 25 percent above their traditional school peers, according to data provided by the California Charter Schools Association.

Independent charter schools have the freedom to operate differently than traditional schools, however: They can require students to earn Cs to graduate, they can have more counselors and lower class sizes, and they have to submit detailed academic five-year plans in order to be authorized, which serve as road maps.

“I’m encouraging the district to look at our schools, including our charters … figuring out what they’re doing and trying to replicate those practices, which the district doesn’t do nearly enough,” Melvoin said.

4 Early intervention.

Cano said a barrier to success with A-G courses is when there isn’t “access to the forward-thinking concentration” on academics across all grades.

“There may be bits and spurts of it right from the early childhood. You may have some really wonderful elementary teachers who are doing the best they can with the resources, and parents who are informed,” she said. “Then middle school gets very complex; parents don’t necessarily know how to navigate for their students in middle school. And there begins separation, specifically in [English language arts] and math. So by the time someone emerges from eighth grade, they’re in the game or they’re not.”

There are college and career coaches assigned to all Title I middle schools, with “a focus on students who display ‘early-warning indicators,’ such as low or inconsistent attendance, challenging behavior as evidenced in discipline reports, and low achievement in math and/or [English],” the spokeswoman wrote in an email. The goal is to strengthen these students’ literacy skills and get them to that C-or-better college standard.

There are 108 such coaches for the 2018-19 school year. The ratio is 790:1 for schools with predominantly minority students and 890:1 for schools with more diversified enrollment.

The district is also piloting “Eighth Grade PASS Intervention Curriculum” for English and math that’s “designed to support students who have failed the Fall Semester in Math or [English], or both,” the spokeswoman wrote. “The courses build academic proficiency, mastery of skills and standards, and readiness for the transition to A-G courses.” Teacher training starts next month.

5 More parent engagement.

“There is a need to actually understand what parents do know” about A-G rates and college eligibility “and inform them of what the reality is,” Cano said. “So then you have parents who want to connect with counselors, who are trying to navigate it for themselves. … You’re also wanting to encourage them to get involved with other parents — because it’s the multiplicity of voices that will result in a structural change.”

6 More local autonomy.

Melvoin said putting more resources into the school sites themselves and allowing principals to decide, “Do I want a library aide or do I want a math coach? What’s going to get us closer to that 100 percent college readiness?” could create a system that better caters to a school’s personalized needs.

All of those things together will hopefully continue to move the needle, Melvoin said.

“It’s not something the district is going to be able to fix overnight,” he said. “But we have to confront deficiencies where they are and hold everyone to a higher standard.”

Taylor Swaak is a staff writer at The 74.