by Evie Blad

California lawmakers stirred up a fierce debate about funding, accountability, and school choice by considering legislation that would put new limits on the state’s charter schools and give districts broader discretion to deny their applications.

The four bills have been closely watched by state and national groups on both sides of the charter school debate, given fresh fire through local activism, charter-skeptical state leaders, and even presidential campaign rhetoric.

California has more charters than any other state and one of the nation’s oldest state charter laws, passed in 1992. It educates about 650,000 students—about 11 percent of its total public school enrollment—in about 1,300 charter schools in urban, suburban, and rural areas, state data show. While the state’s overall student enrollment has declined in recent years, it has ticked up in charter schools.

Supporters of the bills say the number and rapid growth of charters in the state add urgency to calls to update laws to ensure accountability for the publicly funded, privately managed schools and to ensure they don’t negatively affect surrounding school districts. Sponsors of two of those bills have tabled them, while the two remaining proposals are still active.

Charter supporters and charter school operators, who have called the proposals an existential threat, fear the bills will leave approval and renewal of their operations agreements susceptible to shifting political whims. And national school choice backers fear such visible action in such a large state could inspire changes elsewhere.

“You can bet that whatever California ends up passing … if it proves to be as damaging to supporters as it looks now, our opponents will try to export it to other states,” said Todd Ziebarth, the senior vice president for state advocacy and support for the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

Intense National Debate

Nationally, the charter debate has become more intense under the administration of President Donald Trump, in part as national teachers’ unions rally opposition to U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, a highly visible and divisive supporter of school choice.

Encouraged by those unions, some Democratic presidential candidates have criticized charter schools operated by for-profit management organizations. In the most dramatic step so far, Independent Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders released an education plan that calls for a national moratorium on new charter schools until a federal audit is completed.

Sanders’ policy echoes a 2016 call from the national NAACP to halt charter school expansion. But in California, local NAACP branches in San Diego, Riverside, and San Bernardino have voted to oppose a moratorium. Their resolutions cite an achievement gap that splits along racial lines in the state, where a majority of black students are enrolled in noncharter schools.

The California legislative package builds off of the momentum generated by a wave of teacher activism in the state. Los Angeles and Oakland teachers included charter regulations alongside increased pay on their lists of demands when they went on strike in 2018.

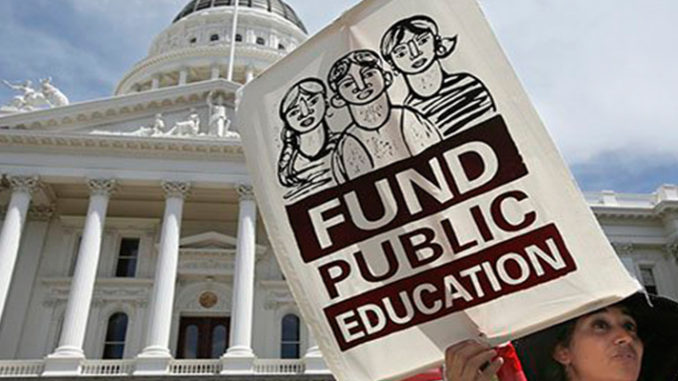

While district schools “are struggling just for survival,” charter schools lobbying against the bills are promoting a “false narrative around school choice,” David Goldberg, secretary treasurer of the California Teachers Association, told thousands of teachers gathered outside of the state Capitol May 22.

“Meanwhile, none of our students have the choice to have a fully funded neighborhood school,” he added. “That’s unacceptable.” The assembled teachers called for increased school funding and put pressure on lawmakers, who later narrowly passed one of the charter bills that day.

That measure, Assembly Bill 1505, would eliminate the ability of charter schools to appeal petition denials to state and county authorizers, which have sometimes overridden district concerns in the past. It would let districts consider the fiscal and facilities impacts alongside academics when a charter applies for approval or reapproval, and allow for approval periods as short as two years. And it would require charter petitioners to explain how they plan to enroll a proportion of English-language learners and special education students that reflects the overall district enrollment.

The Assembly passed the bill by a 42-19 vote.

The other active bill would prohibit counties and districts from authorizing charter schools outside of their boundaries. The two tabled bills would have imposed a moratorium on the creation of new charters and capped the number of charter schools at current levels starting in 2020, only allowing for the creation of a new charter if another one closes in the same jurisdiction.

Supporters of the measures say California’s charter school law has been unchanged for decades, leaving accountability concerns, especially for schools operated far from the jurisdictions that authorize them.

As debate continued last week, the San Diego County district attorney announced an indictment against the A3 network of charter schools. Operators of the schools are accused of stealing more than $50 million from the state by creating “phantom institutions” and falsifying enrollment of 40,000 students, none of whom ever received any services, the Associated Press reported.

Reassurance Falls Flat

Assemblyman Patrick O’Donnell, a Democrat who chairs the Assembly’s education committee and who wrote bill 1505, said “good charter operators” have nothing to worry about under his bill.

But operators of existing charters weren’t comforted. They fear that broader latitude to deny their renewal applications could be abused, and that new caps would squelch the launch of expanded options for families who aren’t satisfied with their school options.

“The needs of our students should always come before politics,” Myrna Castrejón, the president and CEO of the California Charter Schools Association, said in a statement. “We must work together to balance the very real needs of local school districts with the needs of our students who deserve schools where they can learn and thrive. This is especially important in communities where good schools are too few.”

While union members packed the Capitol in support of the bills, charter supporters showed up to urge opposition.

Past attempts to amend California’s charter law have stalled. The winds have shifted in part thanks to a receptive governor. In March, Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, signed a bill that requires charter schools to adhere to the state’s open records and public meetings laws. Similar bills had previously been vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown, also a Democrat. A task force convened by Newsom to analyze charters’ effects will release a report in July.

Similar political shifts could boost charter restrictions in other states, said Ziebarth, of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

“I think it is symbolic, and in some not-so-good ways,” he said.

But some states have also passed bills championed by charter supporters recently. Florida, for example, passed a bill that will require districts to share tax dollars collected through voter-approved referenda with charter schools, and Tennessee lawmakers created a statewide authorizing commission.