by Aaron Churchill

Proficiency standards may feel like a wonky topic, but they have real-world consequences. When students fail to meet rigorous academic targets but are told they are “proficient”—a word whose dictionary definition is “well advanced in an art, occupation, or branch of knowledge”—they may be misled into believing that they’re on a solid pathway to college. This can exert great costs. Misinformed students could, for example, begin coasting through their coursework when they should be pushing themselves to reach higher academic goals. They might begin planning for admissions to college, only to be feel regrets when they can’t get in. And they might skip opportunities that can prepare them for rewarding careers that don’t require four-year degrees.

Unfortunately, proficiency on many state exams has long had little to do with being “well advanced.” In Ohio, for instance, where debate over the issue is beginning to swirl, 66 percent of students met state proficiency standards in eighth grade reading during the 2017–18 school year, even though just 39 percent were proficient according to the more stringent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). In fact, Ohio’s standards are so relaxed that the state cautions that meeting this mark doesn’t indicate being on track for college and career success. (Reaching “accelerated”—a level above proficient—does.)

It doesn’t have to be this. Other states with more rigorous standards—like Colorado, Florida, and Massachusetts—report proficiency rates on state tests that are approximately in line with NAEP levels. Yet for states like Ohio, the worrisome harm caused by low proficiency standards, and the resulting misinformation, affects a large number of students.

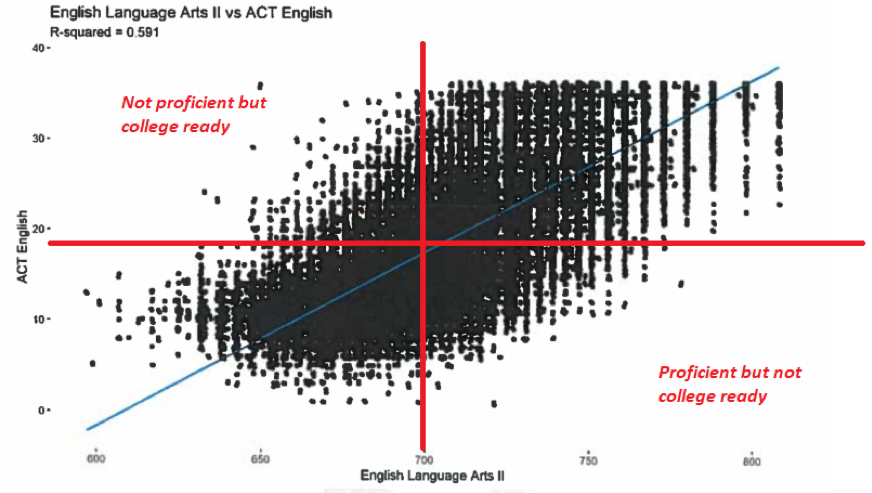

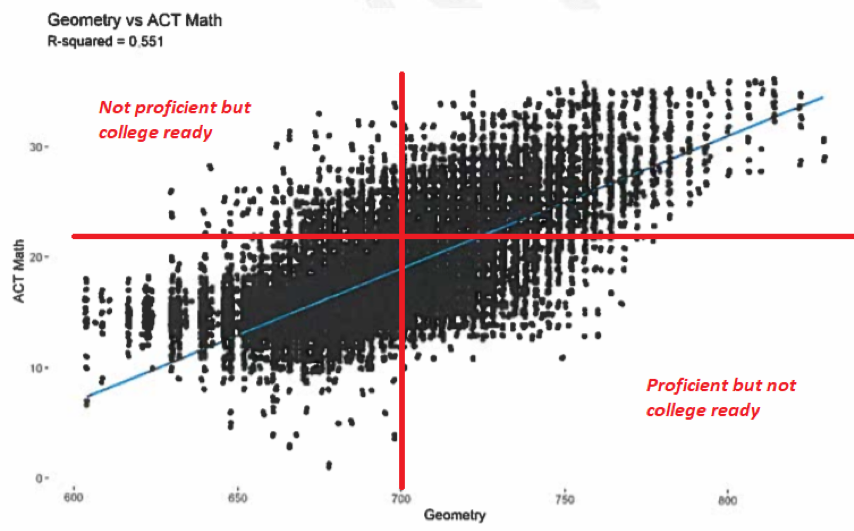

Indeed, a recent, insightful analysis by the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) indicates that such mischief occurs quite often. Consider the following charts, drawn from the agency’s report, that depict the relationship between state end-of-course (EOC) and ACT exam scores. The black dots represent individual student’s scores on the corresponding subject-area tests. Note that these exams were taken by a large majority of students in the class of 2018, the cohort represented in the figures; the EOCs shown here are typically taken during pupils’ sophomore years and the ACT as juniors.

Figure 1: The relationship between Ohio students’ EOC and ACT scores, class of 2018

Note: The red lines indicate the scores needed to reach proficient on Ohio’s EOCs, a score of 700 on both exams, and to achieve college remediation-free scores on the ACT, a score of 18 in English and 22 in math.

Three things jump out from these charts:

- First, we see a positive relationship between the exam scores. As indicated by the upward-sloping blue lines on both charts, students who perform well on state EOCs tend to perform well on the ACT. Though not a perfect, one-to-one correlation, the results remind us that achievement on state exams matters, as they are predictors of performance on college entrance exams.

- Second, in both subject areas, many high-school students are being deemed proficient who do not reach college remediation-free levels on the ACT. This situation is depicted in the bottom right quadrant of the charts where a heavy concentration of dots exists. While ODE’s report doesn’t provide exact numbers, we can see visually that a substantial number of students are deemed proficient on the high-school EOCs—and likely satisfied with their achievement—who don’t reach ACT scores that predict college-level success.

- Third, as depicted in the upper-left quadrant, we see that some students fall short of EOC proficiency but achieve college-ready scores on the ACT. In some cases, it’s possible that disappointing state exam results may have been the wake-up call needed for them to achieve higher scores on the ACT. Thus, there may in fact be a benefit to this type of “misclassification,” rather than the substantial risks involved when overidentifying students as proficient. Moreover, there isn’t a negative impact on these students in terms of graduation, as Ohio recognizes remediation-free achievement on college entrance exams if students struggle on EOCs.

States shouldn’t lead students into believing they are on the pathway to college success when they’re not. For states such as Ohio that have low proficiency targets, policymakers should consider raising the bar so that standards more closely align with college-ready benchmarks. This move that would reduce the number of students who are being told they are proficient but not college ready. In pursuing higher standards, policymakers would need to make clear that these more stringent targets aren’t the high school graduation standard—that should be set somewhat lower than college-ready if state exams are used, as is the case in Ohio. They could also stop using straight-up proficiency rates in its school rating system, relying instead on a performance index for accountability purposes.

Many, maybe most, high school students still aspire to attend college. They deserve the truth about whether they’re on pace to achieve their post-secondary goals. Unfortunately, when it comes to state exam results, the signals seem to be getting crossed, as too many students are being told they’re proficient—suggesting “on track” for college or even “well advanced” in their studies—when they aren’t. In communicating state test results to parents and students, honesty remains the best policy.

Aaron Churchill is the Ohio research director for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, where he has worked since 2012. In this role, Aaron oversees a portfolio of research projects aimed at strengthening education policy in Ohio. He also writes regularly on Fordham’s blog, the Ohio Gadfly Daily, and contributes analytic support for Fordham’s charter-sponsorship efforts. Aaron’s research interests include standardized testing and accountability, school evaluation, school funding, educational markets, and human-resource policies.