The immediate coverage of an important July 2019 study on Latino children in America emphasized how they are increasingly “segregated” from white children at school. Reporters at both Politico and Education Week highlighted that the average Latino child doesn’t interact with white children at school as much as he or she used to. By 2010, the nation’s Latino children attended elementary schools where nearly 3 out of every 10 classmates were white, on average, down from 4 out of 10 in 1998.

In 12 years, that’s a big jump in ethnic isolation. For many Latino children, especially those who live in low-income Latino neighborhoods, the limited contact with white peers is more extreme. The nation’s 10 poorest districts, enrolling at least 50,000 students, were already quite segregated in 1998, and they backslid even further by 2010, the study found. (According to separate federal data, 17 percent of Latino students attended a school that was 90 percent or more Latino in 2010, up from 15 percent of Latino students in 1995.)

But the research team in this new study also calculated that children of different ethnicities and races, including Latino, white, black and Asian students, have become more evenly distributed within the nation’s school districts. It’s hard to express this with a simple number because of the math involved in calculating the even distribution of people. One index of how evenly students of different races and ethnicities are distributed throughout the schools within a district found that the mix improved 21 percent during this 1998 to 2010 time period. Arguably, that’s a big improvement in “integration” and a meaningful decrease in “segregation.”

“These two measures tell you something different,” said Bruce Fuller, a Berkeley professor and lead author of the study, “Worsening School Segregation for Latino Children?” published in Educational Researcher. “White kids might be more evenly spread in schools across a district, but there might be very few white kids to spread around in some districts.”

How can this be? How can Latino children be more evenly spread around the nation’s schools while they’re simultaneously more ethnically isolated?

The answer has to do with population changes and migration patterns.

During this same time period, the number of Latino school children increased from 7 million to 11 million, because of higher birth rates among Latino mothers and Latino immigration. Meanwhile, the birth rate among white mothers fell. The number of white children in U.S. public schools fell from 29 million in 1999 to 26 million in 2010. As Latinos jumped from 15 to 23 percent of the student population, it was inevitable that they’d interact with fewer white students even if you distributed them throughout every school in America. There are simply fewer white students in the school system.

Indeed, Fuller said that a big part of the jump in the ethnic isolation in an average Latino student’s classroom can be explained by the increase in the Latino population and concurrent decrease in the white population. But it doesn’t explain all of it. The isolation jump from 40 percent white students to 30 percent white students is “too large” for that, he said.

What’s driving the rest of the increase in Latino isolation, Fuller believes, is that as Latinos spread around the country, they tend to move to the same neighborhood and send their kids to the same Latino schools with very few white peers. EdBuild, an organization that advocates for equitable school funding, also released a July 2019 report on how segregated schools are by race and income across district lines.

At the same time, Latinos continued to increase their numbers in traditional urban enclaves in New York, Chicago and the Southwest, where they already lived in large numbers. For example, Latino students now comprise more than 80 percent of the Los Angeles school district.

“Any school district that was heavily Latino became more intensely so because of birth rates,” said Fuller. To some, that increase in the concentration of Latinos is “segregation” because a Latino child is less likely to sit next to a white child in school.

Why ethnic isolation matters isn’t clear. Fuller and other academics rely on research dating back to the 1970s, which finds that black students post higher test scores when they have more white peers in their schools. But there hasn’t been as much research on Latino students. And, for the most part, the black students were poor. Their exposure to white students was both an exposure to racial diversity and an exposure to higher income peers. It’s hard, from this earlier research, to determine if the benefit of diversity in education comes from exposure to students of different ethnicities or students of different incomes.

Fuller and his colleagues found in their new analysis that all low-income children are more likely to attend school with middle class peers. About one half of all schoolmates that a low-income pupil sees at school are now from a middle-class background. In 1998, only 4 out of 10 school peers were middle class. That’s a surprise because other researchers have found that school segregation between rich and poor has been increasing. But that rich-poor divide was driven by very wealthy Americans moving to separate neighborhoods away from both poor and middle class people. In Fuller’s analysis, there’s more mixing between poor and middle-income students.

What that means for Latinos is that a low-income Latino child might be in a heavily Latino school with very few white peers, but that Latino child is also exposed to more middle-class classmates than a generation ago. This is happening because second and third generation Latino families are rising up the economic ladder and moving to nicer towns and cities, such as Glendale and Pasadena outside of Los Angeles.

It’s not clear whether Latino children will see academic benefits from this economic integration similar to the benefits that black students saw from attending school with whites.

“We’ve had a half century of research about black and white interaction but we know very little about how to lift Latino kids with an integration strategy,” said Fuller. “Can you get a similar bang when poor Latino kids go to school with middle-class Latino kids? Is the peer effect driven by class or is there something about race? …We’re directly testing that now.” Fuller’s co-author, Claudia Galindo at the University of Maryland, is overseeing this new line of research.

“In the Latino studies world, some say they are so many cultural assets in Latino communities, why would we want to yank our kids out of these schools and send them to schools with white kids?” Fuller added. “Maybe there’s a bigger bang with poor Latino kids sitting with middle-class Latinos instead of middle-class whites.”

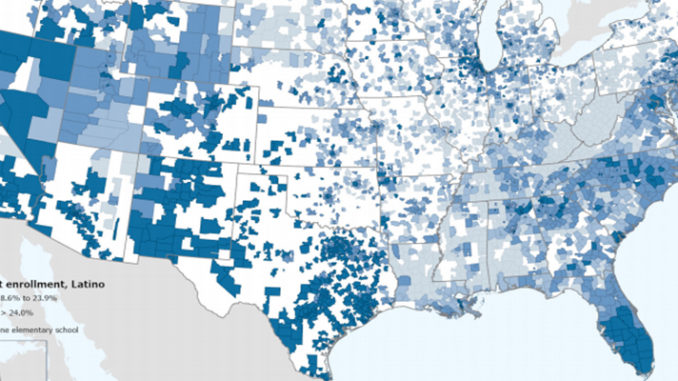

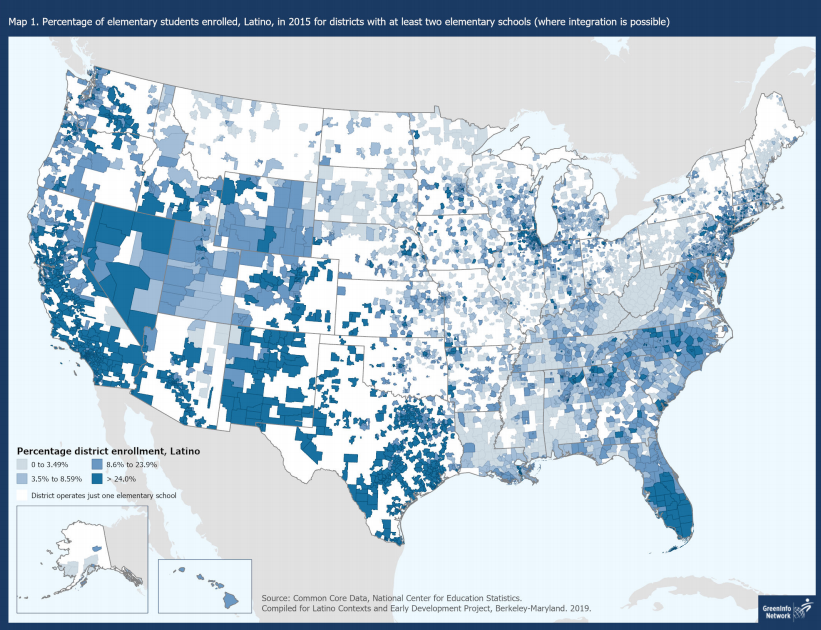

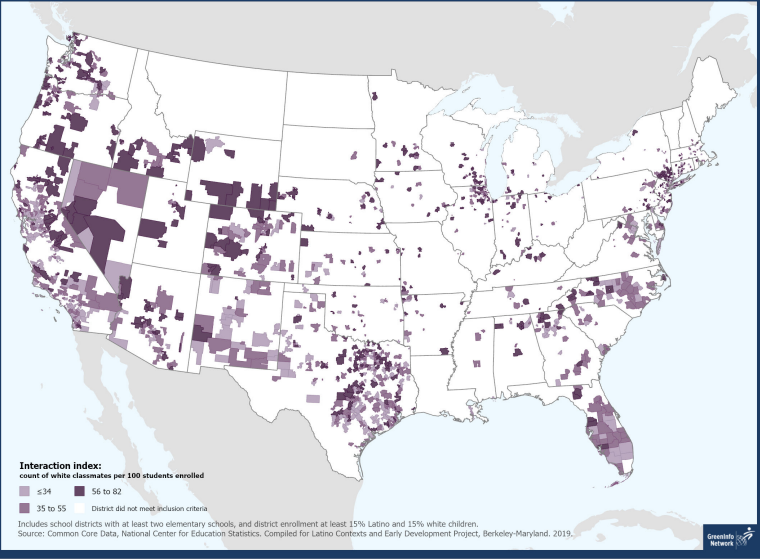

To assist policy makers, Fuller has created a map, highlighting which school districts have sufficiently high Latino and white populations that desegregation investments could be worthwhile. (See purple map adjacent to this story.) Then again, if Fuller’s future research finds that integration of poor and middle-class students is as powerful as racial and ethnic integration, it would be a different map entirely.

This story was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.