by Lara Couturier and Josh Wyner

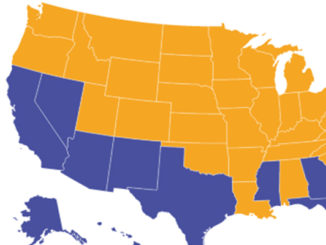

Last week, California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation that will make California the 13th state to provide its residents tuition-free community college. The promise of lower-cost education is great news — for half of U.S. students, the road to a bachelor’s degree winds, at some point, through community college. But an offer of free college will truly transform lives only if colleges and universities take steps to smooth the path from community college to a bachelor’s degree.

For some students — especially those in middle-skills fields like dental hygiene and construction supervision — the credential they can attain in two years at community college will allow them to launch a healthy career, with wages that can support a family. But 4 in 5 students who start community college say they want to eventually transfer and earn a bachelor’s degree. It’s a worthy goal, given that, on average, workers holding a bachelor’s degree earn 40% more annually than those with an associate’s degree.

Yet those aspirations fall far short of reality. Six years after entering community college, only 14% of students earn a bachelor’s degree.

Some students are denied admission to the four-year college they want to attend or don’t receive enough financial aid to make it feasible. Schools often have misguided notions about the competency of community college students, who are well-equipped to succeed in baccalaureate programs, research shows. Students may be admitted to a university but find their previous coursework doesn’t align, in skills and knowledge, to what’s expected at the transfer institution. They may be unable to get into their preferred major because they took the wrong prerequisites or find their credits don’t count toward any major.

Having to take more courses than expected drives up the price and eats up federal financial aid allocation — lowering the chance of obtaining a degree.

More than one-third of undergraduate students transfer during their academic careers, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office. When they do, they often lose nearly 40% of the credits they’ve earned.

This problem does the greatest harm to students the free-college proposals are intended to help the most. Almost half of transfer students come from lower-income families. These students, and students of color, are more likely to enter higher education through community colleges and less likely to obtain bachelor’s degrees.

The failure to ensure smooth transfer widens the opportunity and wealth gaps that plague our nation.

To build more seamless pathways to a bachelor’s degree for students who start in community colleges, barriers to transfer need to be removed at two-year and four-year institutions, both in policy and practice. UCLA, where nearly a third of students transfer from community college, is an exemplar. Staff from admissions counselors to the chancellor engage in outreach with community colleges. UCLA and community college faculty collaborate to address student learning challenges. And the university provides specialized orientation, summer prep programs, mentoring and housing dedicated to transfer students. But UCLA is an exception.

To make the most of free community college, colleges and policymakers in every state should engage in several practices that research shows make a significant difference in ensuring transfer success.

They need to speak out about why improving college transfer success matters and explain why it is critical to providing socioeconomic mobility for students, closing equity gaps, improving college completion and developing the talent that the nation needs. Just as statewide goals for degree completion have impelled colleges to change course, setting goals for improved transfer outcomes — broken down by student characteristics including race and income — and publicly reporting the results is likely to spur improvement.

In the most effective partnerships, faculty and staff from community colleges and the four-year institutions where their students are most likely to transfer meet to understand each other’s academic requirements and map out academic paths for transfer students. Both schools then work to improve advising and other supports so transfer students have the best chance at succeeding. The four-year schools offer community college transfer students the same kind of financial aid packages that they provide to students who started as freshmen. The path to smooth transfer can start as early as high school, where the dual-enrollment process can be designed so that high school students taking community college courses receive credit and make progress toward specific majors.

As free college gains purchase, more states will face a pressing need to fix the transfer dilemma. The first to implement free college will see many more students enrolling in community college and thus face a unique set of challenges. They also have an opportunity to pave the way for others, by testing transfer approaches that are making a difference at the few schools already engaging in them.

If states and schools are successful, they will significantly increase bachelor’s attainment rates for community college transfer students and take a major step toward improving opportunity for those often disadvantaged by our education system. If nothing is done, free community college may not turn out to be all that free — but a costly detour instead.

Lara Couturier is a principal at HCM Strategists. Josh Wyner is vice president of the Aspen Institute.