by Natalia Molina

U.S. immigration policy today offers a parade of horrors: Children caged in detention centers. Family separations. ICE agents dragging parents away from the school dropoff. Rules stiffened to deny green cards to immigrants for using food stamps or housing vouchers. Looking at these outrages, as some have noted, it seems the cruelty is the point.

True enough. But this specific kind of cruelty — the deliberate targeting of families — also has a point. The logic behind it, and its long history in American policy, holds that the biggest danger of immigration is women and their children.

California voters made this particular point 25 years ago, when they approved Proposition 187 on Nov. 8, 1994. That ballot initiative — had it not been stayed by federal courts — would have denied public education, healthcare and other state services to immigrants who were undocumented.

Supporters of 187, including then-Republican Gov. Pete Wilson, invoked the ugly stereotype of the “anchor baby,” the idea that immigrant mothers, especially Mexicans, illegally enter the United States in droves to give birth at U.S. taxpayers’ expense, with the goal of securing citizenship and other public benefits for themselves and their babies.

Targeting services most essential to families with children, and accompanied by an outburst of proposals to end birthright citizenship, Proposition 187 specifically aimed to foreclose Latino families’ ability to take shape or take root here.

The impulse to deny public services to immigrant families dates back much further than 1994, to at least the 1930s and the Great Depression. Immigration law at the time was focused on the idea that newcomers were a drain on public resources, a charge again echoed in Proposition 187 rhetoric, despite evidence that immigrants with and without papers were contributing to the tax base. In 1930s parlance, anyone who received “charity” within five years of entering the U.S. was deemed deportable.

Predictable family separation tragedies followed, and Congress wasn’t completely immune from them. In May 1935, debate began on a bill that would have allowed immigrants of “good moral character” with no criminal offenses to escape deportation, and to move toward citizenship, even if they had used charity.

In theory the bill — which didn’t pass — would have protected all immigrant families, but it seems to have been intended primarily to benefit Europeans. One senator argued that it was inhuman to send immigrants back to Germany or Russia given the political situations in those countries. Newspapers ran stories with headlines such as “Exempt the Worthy Here Illegally” and sympathetic accounts of ethnic white families “shattered, lives broken, and the possibilities of producing worthwhile citizens … routed, all without reason.”

There was little similar sympathy for Mexican immigrants. For them, the Depression was a time of mass repatriations, deportations and general scapegoating.

In 1935, the Los Angeles Times ran an article entitled “Family of Ten Sent Back to Mexico,” which featured a photograph of Simon Alvarado, his wife and their eight U.S.-born children. There was no discussion of this family’s “broken” life, or even of the Alvarado children’s rights as American citizens. Instead, the reporter quoted an immigration officer, M.H. Scott, who described the family’s deportation as designed “to relieve taxpayers of the burden of supporting persons not entitled to relief.” The Alvarados, said Scott, were “a class of aliens” the government was working to “eliminate.”

“Relief” encompassed many things a family of modest means might need. An immigrant could become deportable by giving birth at Los Angeles’ County Hospital or seeking emergency care there, by making use of a municipal tuberculosis clinic, or by needing aid to bury a child who died. Children’s citizenship was trumped by a parent’s status. In effect, a U.S.-born child could not access resources intended for citizens without risking having his or her own citizenship revoked through deportation. The upshot was to exclude Mexican Americans and their families from American soil and American identity.

Twenty-five years ago, Proposition 187’s attempt to do much the same thing was ultimately declared unconstitutional in federal district court. Some believe the hysteria of the initiative campaign marked a cathartic tipping point in California, turning voters — especially younger voters — against the GOP and cementing a progressive, pro-immigrant majority in the state.

But it’s worth remembering that in 1994, the majority of Californians were more than willing to adopt cruelty against immigrant families as state policy. Proposition 187 passed 59% to 41%. Then, as now, the motive was less about exerting the rule of law or determining who deserves access to public resources, and more about trying to limit who gets to be an American.

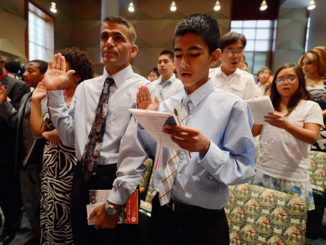

Immigrant families indisputably change the fabric of U.S. society. We have to decide — over and over, it seems — whether to reject that change as a threat or embrace it with open arms.

Natalia Molina is a professor of American studies and ethnicity at USC’s Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. .