Governor Greg Abbott is doing his part to stoke the long-smoldering fires among the Texas Republican electorate. When he responded to President Biden’s characterization of his recent decision, along with other governors, to rescind mask mandates as “neanderthal thinking” in numerous national media appearances last week and an attention grabbing Tweet, migrants and immigration were central to his push back. Abbott accused the Biden administration of “bringing people with COVID-19 and releasing them into the community” in a very animated and widely covered interview on Houston’s KPRC.

The timing of the mounting problems on the border is politically propitious for Abbott. Polling data suggests that the Republican base, significant portions of which have never been as concerned as other Texans by the threat of the pandemic, are already turning their attention to the much more familiar perceived dangers of border security and immigration.

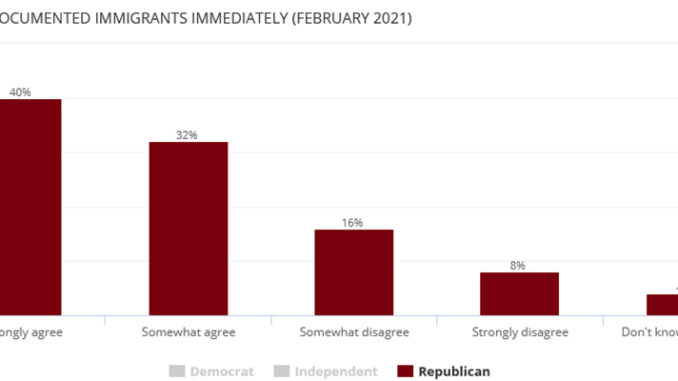

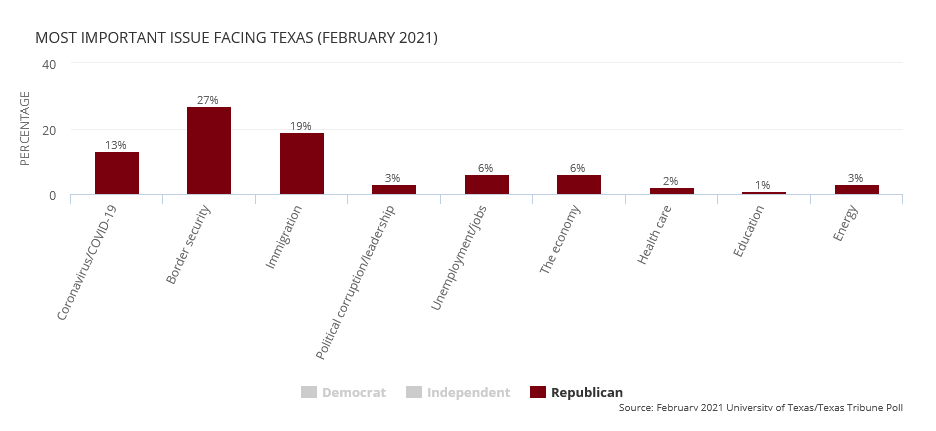

Signs of the latest surge in Texas Republican’s perpetual preoccupation with immigration and the security of the border with Mexico abounded in the February 2021 UT/Texas Tribune Poll. At the most general level, immigration and border security return to their high ranking of problems facing the state. While the plurality of Texans, 23%, said that the coronavirus pandemic was the most important problem facing Texas, 25% said either border security (14%) or immigration (11%). Among Republicans, the share who said either immigration or border security was significantly higher, 46%, dwarfing the 13% who see the ongoing pandemic as the state’s most pressing concern.

Concern over the border and immigrants also ranked high in an open ended question designed to capture Texans’ priorities for the Texas Legislature (such as they exist). COVID-19 topped the list of priorities for the legislature to address, raised without prompting by 22% of Texas voters. But immigration and border security closely followed, mentioned by 14% of Texans as not just an issue for the legislature, but their opinion of what should be the legislature’s top priority. Again, the plurality of Republicans said immigration and/or border security, 24%, twice the share who said COVID, 12%, and 24 times the share of Democrats who said immigration and/or border security (1%).

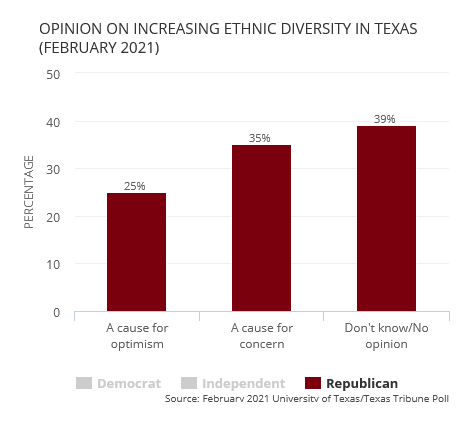

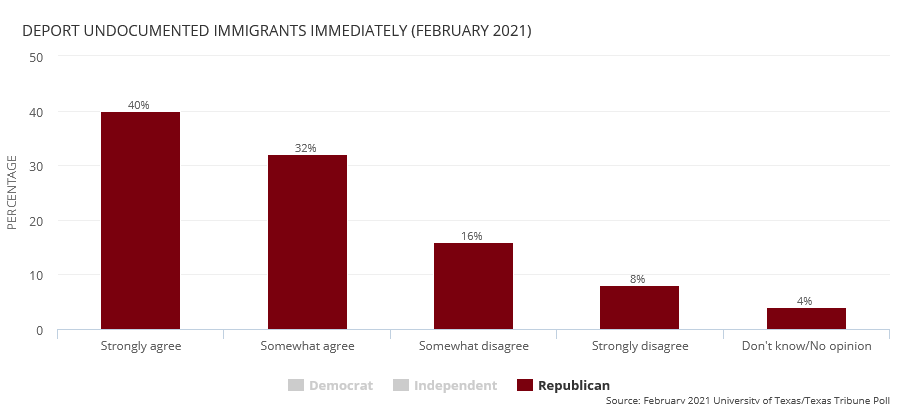

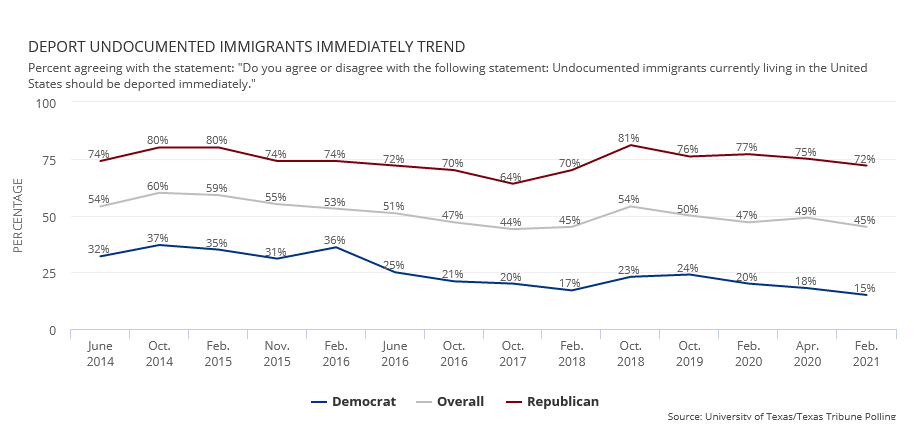

Beyond the pride of place Republicans award to keeping non-citizens out of the country and the border secure, the content of their positions continues to convey a prohibitionist if not punitive attitude towards people born somewhere else. Asked whether undocumented immigrants currently living in the U.S., estimated to number more than 10 million people overall, including more than 1.5 million in Texas, should be deported immediately, 72% of Republicans say that they should, including 40% who agree strongly. Asked whether Texas’ increasing racial and ethnic diversity is a cause for optimism or a cause for concern, only one in four Republicans say that this inevitability is a cause for optimism, while nearly equal shares say it is a cause for concern, or aren’t sure whether or not to be optimistic or concerned.

Beyond the pride of place Republicans award to keeping non-citizens out of the country and the border secure, the content of their positions continues to convey a prohibitionist if not punitive attitude towards people born somewhere else. Asked whether undocumented immigrants currently living in the U.S., estimated to number more than 10 million people overall, including more than 1.5 million in Texas, should be deported immediately, 72% of Republicans say that they should, including 40% who agree strongly. Asked whether Texas’ increasing racial and ethnic diversity is a cause for optimism or a cause for concern, only one in four Republicans say that this inevitability is a cause for optimism, while nearly equal shares say it is a cause for concern, or aren’t sure whether or not to be optimistic or concerned.

There are limits to the GOP’s antipathy toward immigration, and even minor signs of softening of the previously measured intensity of anti-immigration sentiment. The share of GOP voters in Texas that would immediately deport over a million people currently living in the state is fairly static. Asked the same question 13 times since June of 2014, the share of Republicans who endorse immediate deportation peaked at 81% in October 2018, and has tended to stay in the mid-60s to mid-70s. Looked at in this context, the 72% who called for immediate deportation as of February is in the lower end of the typical majority share of GOP responses to the question — but expect this to fluctuate if and when the border captures more national and statewide attention.

When the frame shifts from immigrants generally to those immigrants whose undocumented status isn’t a fault of their own, and who are “doing the right thing,” these general attitudes soften. For example, when asked whether DACA, described as, “a program begun in 2012 [that] prevents the deportation of young people who were brought to the United States illegally as children, completed high school or military service, and have not been convicted of a serious crime,” a plurality of Republicans, 46%, would continue the program, while 40% would end it. This in itself is a softening from three years earlier in February 2018, when a majority of Texas Republicans said the program should be ended (51%), and the near majority who said the same in October 2017 (48%). In February 2021, 63% of all Texas voters would continue the program, only 25% say the program should be ended.

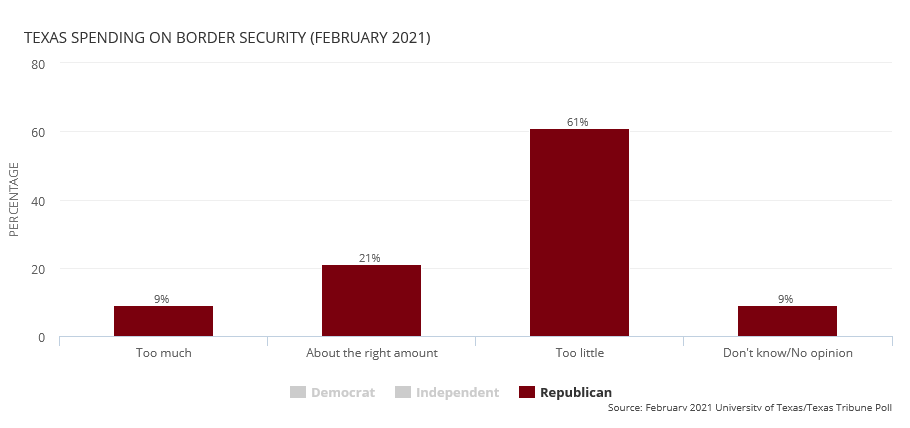

When considering the broad attitudes at work here, the positions Republicans take towards family and children in the context of immigration appear a reluctant response to failed efforts to keep non-citizens out. The February poll found ample evidence of otherwise thrifty Texas Republicans willing to spend their hard-earned tax dollars to shore up the border. In an item gauging perceptions of the state’s financial commitment in a number of areas as the legislative session gets underway, 61% of Republicans said that the state spends “too little” on border security, the highest share of Republicans expressing this opinion in any of the nine policy areas tested, and a domain in which the state government has repeatedly spent large sums of state dollars — even though immigration and border security is, by definition, a federal responsibility. Border security was the only area in which a majority of Texas Republicans opined that the state spends too little. For a few points of comparison, the next highest area of financial need, according to Texas Republicans is state spending on mental health services, with 44% saying the state spends too little, followed by K-12 education (31%), and transportation (25%) — only 20% of Texas Republicans think the state has spent too little on its COVID response.

Not to get too hermeneutical, but it’s hard not to be struck by the intensity of Abbott’s affect in the aforementioned KPRC interview immediately after he announced that Texas was 100% open. The interviewer, doing his job, focused on getting Abbott to make the case for policy changes at odds with virtually all public health advice. Abbott turned uncharacteristically combative with the interviewer, seemingly intent on making sure the message that the Biden administration was flooding Texas with “COVID-19 infected immigrants” was greeted with sufficient outrage (and airtime), particularly after the interviewer resisted the governor’s attempt to redirect the emphasis of the conversation toward Abbott’s rescinding of the COVID-19 public health order.

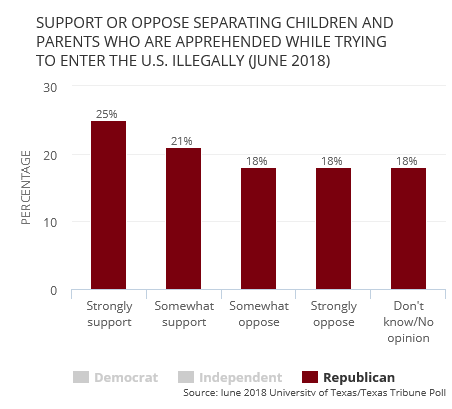

Abbott’s point had a grain of truth, and had been promoted earlier the same week by a Democrat, Congressman Henry Cuellar of Laredo. The politics of Cuellar’s play are a subject unto themselves, given the congressman’s position in his party. But the fact that some of the immigrants released as a result of the Biden administration’s policy changes had tested positive for COVID-19 does point to important context of the reemergence of immigration as a means of rallying the Republican troops in times rendered uncertain for them by Trump’s defeat in 2020, the pandemic, and the recent infrastructure and policy failures in the state. There *is* another humanitarian and policy crisis unfolding on the Texas-Mexico border, one that threatens to have the same characteristics that elicited trenchant criticism from Democrats during the Trump presidency and triggered cross pressures such as those described above among Republicans. In June 2018 UT/TT polling, Texans were asked whether they “support or oppose separating children and parents who are apprehended while trying to enter the U.S. illegally?” Overall, a majority, 57%, opposed this policy (including 44% strongly) while only 28% supported it, but the policy split Republicans, leaving 46% in support, 36% opposed, and 18% unsure — a far cry from the overwhelming support found for most punitive immigration policies that don’t involve children.

Abbott’s point had a grain of truth, and had been promoted earlier the same week by a Democrat, Congressman Henry Cuellar of Laredo. The politics of Cuellar’s play are a subject unto themselves, given the congressman’s position in his party. But the fact that some of the immigrants released as a result of the Biden administration’s policy changes had tested positive for COVID-19 does point to important context of the reemergence of immigration as a means of rallying the Republican troops in times rendered uncertain for them by Trump’s defeat in 2020, the pandemic, and the recent infrastructure and policy failures in the state. There *is* another humanitarian and policy crisis unfolding on the Texas-Mexico border, one that threatens to have the same characteristics that elicited trenchant criticism from Democrats during the Trump presidency and triggered cross pressures such as those described above among Republicans. In June 2018 UT/TT polling, Texans were asked whether they “support or oppose separating children and parents who are apprehended while trying to enter the U.S. illegally?” Overall, a majority, 57%, opposed this policy (including 44% strongly) while only 28% supported it, but the policy split Republicans, leaving 46% in support, 36% opposed, and 18% unsure — a far cry from the overwhelming support found for most punitive immigration policies that don’t involve children.

It seems unlikely that the Biden administration will be any more effective in responding to this crisis, practically or politically, than the last three presidential administrations, who were all vexed by what is indisputably a complex, recurring, and painful policy problem. In an interview segment featured on new, D.C. insider fest Punchbowl, Biden’s chief of staff Ron Klain soberly assessed the situation the Biden administration faces:

Look, I think we inherited a real mess. We inherited the facilities we have….we are doing our best to surge capacity to the border, particularly for these children who arrived here without parents, to house them in a way that is safe, to house them in a way that’s humane and help ultimately reunite them with either family they have in this country or sponsors who are willing to take them in in this country. That takes time and that is not something you can do overnight.

In ruthless political terms, the Biden administration’s announced intention to push comprehensive immigration reform even as it is forced to grapple with perennial problems on the border are all the better for Texas Republicans, and they know it. Abbott’s heated response to Biden’s criticism and the rush of Republicans looking to stage photo ops at the Texas border demonstrate the political reflexes of Republican elected officials eager to resume a unifying call and response with their base voters.

When Donald Trump declared his candidacy for the presidency in 2015 by denouncing the alleged failure of America to protect its citizens from criminal immigrants, it marked the ascension of Trump’s, and the party’s, louder, brasher approach to what had been Texas Republicans’ carefully choreographed appeals to their base’s preoccupation with border security and immigration even as they managed the politics of an increasingly competitive majority minority state. Trump took their issue, and escalated the hostility through his rhetoric and willingness to pander to the expectations of voters eager to build that wall, with nary a thought to the considerations of future demographics or the bounds of civility that have led at least some Texas Republicans, including Abbott, to at least occasionally attempt to temper their appeals with Spanish language ads or lip service to the diversity of Texas’ culture (at least after the primaries).

Abbott’s angry exhortation in that KPRC interview last week that the new president “is bringing people in with COVID-19 and releasing them into our communities” — repeated with rising volume and intensity — was denounced by critics as “xenophobic” and even “hypocritcal.” But the political opportunities the situation offers are as clear as is the embrace of Trump’s nativism and his immigrant bashing by the millions of Texas Republicans who voted for him in the last two presidential elections. While there might have been something slightly unhinged about the governor’s resort to the all-too-familiar fiction of an invading army of immigrants spreading crime and disease mere minutes after blithely moving on from any but the most nominal effort to contain the continuing pandemic, the governor knows that Trump’s exit from the White House leaves more room at center stage — and knows very well what the audience wants to hear as he tries to seize it.

.

.