Duncan Wood, Director, Mexico Institute, Wilson Center, Washington, DC.

Does the implementation of the USMCA create more opportunities for partnership or conflict in North American relations?

July 1, 2020 is a historic day. The coming into force of the USMCA, North America’s new regional trade agreement, has the potential to propel each of the three member countries individually, and the region collectively, to the highest levels of international competitiveness. After lengthy, and at times tortured, negotiations, the governments of North America agreed on a framework for trade and investment in the region that addresses many of the failings of the original NAFTA, while at the same time updating and modernizing the regime to meet the demands of the 21st century economy.

Of course, the agreement is far from perfect. Certain elements of the text referring to regional content, minimum salary levels, and relations with non-market economies are a departure from the original free trade spirit of the NAFTA. But the negotiation and eventual ratification of the USMCA was always going to be an exercise in the politics of the possible. To quote Mick Jagger, “You can’t always get what you want; but if you try sometimes, you just might find, you get what you need”.

Although the negotiation and ratification of the agreement was hard work and at times seemed to be destined to fail, now that USMCA is a reality there is still an enormous amount of hard work to be done. Legal and regulatory frameworks will have to be adjusted, there will be friction and obstacles for many companies as they come into force, and we should expect a slew of trade conflicts based upon the new rules. For these reasons, a huge amount of effort from both public and private sectors in all three countries will have to be dedicated to making sure that the new free trade agreement works well.

Having said this, there is a real opportunity for the North American partners to move beyond conversations about trade and investment. Now that the rules have come into force, we need to push our three countries’ leaders to think beyond trade. There needs to be an investment of time, effort, and political capital in addressing issues as diverse as energy integration, climate change, citizen security, organized crime and drugs, and ensuring that the region as a whole is prepared to face exogenous and endogenous threats. We need to invigorate the dialogues that have taken place thus far on a bilateral basis in the areas of security and defense, human capital development, and labor mobility. There is an urgent need to review the region’s pandemic preparedness and for the three governments to work together well to continue to defend their citizens from the threat of terrorism. In the immediate future, we have to focus on the need to ensure that democracy is safe from disinformation and election meddling.

It is true that we have much to celebrate. Only four years ago, it seemed impossible to renegotiate NAFTA; now, we have a new agreement. However, while we raise a glass to the successes of the past few years, let us also think ahead to even closer cooperation and collaboration between the North American democracies.

Christopher Sands, Director of Canada Institute, Wilson Center, Washington, DC.

How will the USMCA affect Canada and what can Canadians do to contribute to its success?

Implementation of the USMCA ends nearly four years of uncertainty about Canada’s market access to the United States that held back Canadian economic growth even before the COVID-19. As a result, Canada Day 2020 will be a date to celebrate as one giant step toward economic rebound. The bipartisan majorities in the U.S. Congress that voted in favor of the USMCA are another encouraging sign that a new U.S. trade policy consensus may emerge in Canada’s largest export market. U.S. political leaders in Washington and state capitals across the country had their eyes opened to the value of Canadian investment, purchases of U.S. exports, and support for U.S. jobs thanks to Canada’s outreach during the USMCA negotiations, which will pay dividends for U.S.-Canadian relations for some time to come.

Over 25 years NAFTA lost support because critics’ concerns went unanswered and many U.S. political and business leaders chose not defend the agreement or highlight its benefits. In Canada, where governments and the private sector did address critics and defend NAFTA, public support for free trade rose steadily and in the 2019 federal election none of the party platforms called for Canada to withdraw from NAFTA. Instead, parties competed over who would best safeguard Canadian access to the U.S. market.

Now the work begins: we must track USMCA implementation, identify problems and solutions, and seek opportunities to make that market work better so that when the three countries review the USMCA in 2026 we can keep it going strong.

Arturo Sarukhan, Global Fellow & Advisory Board Member, Mexico Institute, Wilson Center; Former Mexican Ambassador to the United States, Washington, DC.

The USMCA is being implemented while the United States election begins to heat up. How will these two processes interact, and what will be the impact on U.S.-Mexico relations?

In the medium term, there’s both good news and bad news going forward. The good news is that the overwhelming bipartisan support for ratification of the UMSCA in Congress, along with President Trump’s crowing that it is the “best-ever” agreement negotiated by the United States, ensure that it will not be used, unlike the 2016 GOP campaign in particular but also in previous electoral cycles with Democrats, as an electoral piñata in the runup to Election Day. However, the bad news is that current political dynamics in both Washington, DC, and Mexico City provide anything but certainty.

On the one hand, if the long-awaited debut of the revamped trade pact with Canada and Mexico heralds a new dawn in North American relations and for regional rules-based trade, the Trump Administration sure has a funny way of showing it. Regardless of the entry into force of the USMCA, Trump will continue to wield punitive and mercantilist measures to extract concessions from Canada or Mexico. A case in point are the recent threats regarding Section 232 aluminum and steel tariffs on Canadian exports to the United States, or Trump’s assertion suggesting an end to live cattle imports in an effort to affect producers hurt by disruptions in the supply chain -when Mexico and Canada are the only two countries that export to the United States- in violation of impending UMSCA rules and disciplines. With Trump cornered by negative polls, a struggling economy, and spiraling COVID-19 deaths amid a pandemic that appears far from under control, pimping trade issues to score electoral points will be a recurrent temptation for him. On the other side, the López Obrador government -and his MORENA coalition in Congress- continue to push abrupt policy shifts and changes to the rules across different sectors of the economy that bode ill for the level playing field required under NAFTA and its successor, the USMCA.

Earl Anthony Wayne, Public Policy Fellow & Advisory Board Co-Chair, Mexico Institute, Wilson Center; Former U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, Washington, DC.

How can USMCA be used as a platform for further efforts to strengthen North American competitiveness?

USMCA should strengthen North America’s ability to compete with global rivals in a variety of ways that reduce barriers to trade, to joint-production, and to strengthening the ability of already existing supply chains to become more efficient and more resilient.

This opportunity is embodied in new provisions and mechanisms that should facilitate the flow of goods and services at the borders, for example, if the three countries can improve digitalization and speed of customs procedures. Increased competitiveness should be evident in the application of new disciplines regarding cross-border data flows and services, since increasingly the internet will be the gateway for providing services and for managing efficiently production and logistic networks, for example. The new agreement also provides for enhanced regulatory cooperation which can significantly reduce costs in the vast co-production networks across the continent and provide savings for consumers while assuring that safety and health concerns are well addressed.

One of the most promising potential mechanisms in USMCA is the establishment of a Committee on Competitiveness. If the three governments use this new committee to look seriously at the factors, steps, and policies that can increase competitiveness across North America, this dialogue could help make USMCA a forward-looking agreement which helps open opportunities for future growth and prosperity. One of the areas that I have highlighted for discussion is policies and practices that encourage investment in workforces so they can gain the skills needed for the rapidly evolving, technology-powered workplaces across the continent. The labor section of USMCA also opens the door for such valuable work on workforce training and education.

Luis Rubio, Global Fellow & Advisory Board Member, Mexico Institute, Wilson Center; President, COMEXI, Mexico City, Mexico.

NAFTA provided certainty for investors both through its specific investor protections and because it forced Mexican leaders to commit to stay the course on economic reforms. Can the USMCA provide similar certainty today?

The only true similarity between NAFTA and the new USMCA is the fact that both establish rules for trade and investment across the two North American borders. Beyond that, these are two quite distinct legal documents. NAFTA was meant to be a mechanism whereby the United States provided guarantees for investors in Mexico with the objective to accelerate Mexico’s development while deepening the economic ties across the three nations. The ulterior objective was to strengthen America’s border, which stemmed from the notion of Mexico as a primary national security interest. A prosperous Mexico, the then American president argued, is in the best interest of the United States. The primary objective of NAFTA was strategic and political. USMCA is above all a compromise on trade.

USMCA not only eliminates the guarantees for investors but creates disincentives for new capital to flow into Mexico through a series of mechanisms, including very tight rules of origin, severe penalties for labor practices, and (very high) minimum wages for a series of industrial processes. In addition, the agreement incorporates a sunset clause after every six years, a circumstance that hinders long-term projects from being contemplated. Clearly, the two documents pursue different objectives.

Most of the emphasis of the USMCA is placed on both updating the old agreement to incorporate the novelties of one of the fastest-changing periods in history, especially with the introduction of the Internet, online commerce, just-in-time delivery (as part of dynamic industrial supply chains that crisscross the region), and all things digital. On the other hand, the agreement incorporates a series of measures to introduce political change in Mexico, particularly as it attempts to dismantle the old labor-union structures that for decades were one of the staunchest support mechanisms of political stability. Whether the pretense of introducing democracy into the labor arena will deliver what the two governments want (which most likely is not the same thing) remains to be seen. What the López Obrador administration certainly wants is to replace the existing labor structures with his own, to then bring them over as social control systems within its own coalition.

To answer the question in one line, there is no way that the new USMCA will provide for long-term economic growth and political certainty because it is not meant to accomplish that. At best, it will protect, for a while, Mexico’s foremost engine of growth, namely exports of manufactured goods, and not even that is certain. Much ado about nothing wrote Shakespeare. Something similar may well be waiting for USMCA, albeit with much bigger, probably dire, consequences.

.

Christopher Wilson, Deputy Director, Mexico Institute, Wilson Center, Washington, DC

Will implementation of the USMCA stimulate a recovery of the Mexican economy?

The Mexican economy was already stagnated, with around -0.1% growth, in 2019. Then came the COVID-19 pandemic, which pushed Mexico over the edge into an economic freefall. By April 2020, Mexico’s INEGI measured economic activity at a level last seen in 2010, meaning a decade of growth was wiped out in a matter of months. By May, Mexican exports were less than half what they were in the same month of 2019. Mexico appears to be at right around its peak in terms of COVID-19 cases right now, and parts of the country are beginning to reopen. As transmission slows, the speed of Mexico’s economic recovery will be vitally important in mitigating the impact on poverty and job loss across the country.

AMLO and other Mexican officials have touted the USMCA as a key part of their plan to stimulate the recovery. With only a very modest fiscal stimulus, a lot is riding on whether this pans out. Is this realistic? Well, trade will certainly recover as the economies of North America reopen, and the speed of the U.S. recovery will play an important role in driving demand. But the Mexican economy faces a deeper challenge regarding investment. In 2019, foreign and especially domestic investors were hesitant to pour their money into the Mexican economy. They were unsure what the future would bring. Some of that may have had to do with the outlook regarding the ratification of the USMCA in the United States and the future of regional trading relations, but much more was the result of the transition to a new government in Mexico, which caused both policy uncertainty and a natural slowdown in government spending as fiscal priorities were adjusted.

In this context, the implementation of the USMCA does indeed represent a restoration of some certainty for investment in the North American economy. It will help, but it is no panacea. To really speed up the recovery and save millions of Mexicans from falling into poverty, the Mexican government needs to increase government investment and commit to an overhaul of its currently tense relationship with the private sector.

Roy Norton and Deanna Horton, Global Fellow, Canada Institute and Senior Fellow, University of Toronto Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, Canada

What challenges or opportunities do you see for North American competitiveness and collaboration with the implementation of USMCA and its cross-border trade in services chapter?

Chapter 15 of USMCA/CUSMA/T-MEC (Agreement) provides some welcome updating of NAFTA in certain services sectors. The expansion of recognition protocols for professional services will create opportunities for greater commercial links and greater efficiencies among the signatories. The section on SMEs contains for the most part hortatory language, but at least acknowledges the important role of SMEs in fostering commerce and encourages the signatories to ease undue regulatory burdens.

This response focuses on Annex 15-B which creates a ‘Committee on Transportation Services’ (Committee) with a reasonably open-ended mandate. So while the Agreement does not eliminate or reduce existing protectionism of cabotage (“trade or transport in coastal waters between two points within a country”), the Committee presents an opportunity for governments to have some serious discussion about it– hopefully with the will to lift from the integrated North American economy the heavy cost burdens associated with Canada’s Coastal Trading Act (CTA – which dates from 1989) and the USA’s Jones Act (JA – which was 100 years old in June, 2020).

In 2002, the U.S. International Trade Commission projected an annual economic gain to the United States of between $5 billion and $15 billion if the JA were repealed.[1] Recently, it has been estimated that by encouraging the use of older, less energy-efficient vessels, the JA engenders environmental costs exceeding $8 billion per year.[2] The JA and CTA have particularly disadvantaged the economies of the eight states and two provinces bordering the Great Lakes St. Lawrence Seaway System (GLSLSS). The competitiveness of the highly integrated steel and auto industries, both with heavy concentrations in the GLSLSS, is challenged by the unnecessarily higher costs associated with cabotage protectionism.

The pandemic has underscored the importance of supply chain resilience, and both the United States and Canadian governments have declared ‘reshoring’ supply chains a priority. The JA and CTA actually impede that goal (they advantage goods manufactured abroad and imported to the continent on foreign-flagged vessels). Successful reshoring means fewer imports and more goods manufactured here – whose competitiveness with imports, however, would be compromised by the higher-than-optimum shipping costs they would bear in moving around the continent. Weakened by the global recession, it’s time for the United States and Canada to resolve that they should no longer ‘afford’ such counterproductive protectionism.

The Committee envisioned by USMCA Chapter 15 has scope to focus on how the three economies could amend their statutes, per Article 15.3, to accord National Treatment to U.S.-, Canadian-, and Mexican-flagged shippers. Perhaps the Committee could also take up related issues such as harmonizing safety provisions and other regulations. Still not the optimum result which would be full repeal of the JA and CTA, but a start in line with the Agreement’s objectives.

A longer piece on this subject, co-authored by Deanna Horton and Roy Norton, will soon appear on the Canada Institute’s website.

[1] Bellemare, Louis, Citing U.S. ITC ‘The Economic Effects of Significant U.S. Import Restraints, Third Update’, 2002, in ‘Jones Act, A Missed Opportunity for NAFTA’, The New Maritime World: a site on the Maritime Economy, Jan. 5, 2018. http://nm-maritime.com/en/jones-act-a-missed-opportunity-for-nafta/

[2] Fitzgerald, Timothy. ‘Environmental Costs of the Jones Act’. CATO Institute, March 2, 2020. P.1.

Andrew Selee, Senior Advisor & Advisory Board Member, Mexico Institute, Wilson Center; President, Migration Policy Institute, Washington, D

The USMCA negotiations left NAFTA, or TN, visas in place and unchanged. Is a North American conversation on labor mobility and migration possible in the years ahead?

Mobility and migration was barely touched in the renegotiation of NAFTA that produced the USMCA, except to leave in place the professional visas (called TN in the United States) that have been a useful tool for the movement of skilled Mexicans, Americans, and Canadians among the three countries. That is as it should be. Trade agreements are never really the right venue to negotiate migration deals, and the U.S. Congress has long frowned on the practice. But getting economic integration right will eventually require sensible policies on migration that are negotiated among the countries, often in bilateral agreements or simply implemented in national legislation. It will require thinking more critically about temporary worker programs, which have been quite successful at creating legal channels for Mexican workers to work short-term in the United States, but need long-term reform to be more agile for both workers and companies (along the lines negotiated among growers and farm workers, for example). And it will require restoring a sense of shared management of the U.S.-Mexico and U.S.-Canadian border, including policies on asylum and dealing fairly and effectively with third-country nationals who migrate to the shared borders. It’s hard to imagine those discussions right now, but they will be needed in the future.

Lisa Raitt, Global Fellow, Canada Institute, Wilson Center; Former Conservative MP, Toronto, Canada

As the auto sector responds to changing attitudes towards transportation, what challenges or opportunities do you see for the auto sector (or transportation sector) with the implementation of USMCA?

Even before COVID-19 shone a light on the fragility of global supply chains, there was a keen focus on the impact of USMCA on the automobile industry and its supply chain.

The USMCA requirement that North American content be gradually increased from 62.5% to 75% was viewed as an incentive to automakers to increase the amount of North American parts used in their cars and light trucks. As it was thought that the increase in content would also increase production costs, automakers were reviewing their supply chains to find cost savings which included sourcing from suppliers nearer their North American assembly plants.

Having now seen the effect the COVID-19 pandemic has had on global supply chains, their review should take on a more focused approach. Automakers may want to look at supply chains and analyze not only cost savings but also resilience: whether a disruption in certain geographic areas (China, South Korea, Japan, etc.) causes a shortage of supply in critical components and an overall impact on production. Where a risk to the supply chain is noted, the automaker could develop a strategy for alternate sourcing which includes local suppliers.

In Canada, the Deputy Prime Minister, Chrystia Freeland has already indicated that in the context of the impact of COVID-19, she sees supply chains shifting closer to home. In Ontario, lawmakers are already preparing for these changes. In December of last year, the Ontario government launched a strategy to attract large-scale investments to build auto or other advanced-manufacturing plants. This was in addition to a program announced in Fall of 2019 to help auto parts manufacturers modernize their technology.

With the trade agreement coming into force on July 1, USMCA is viewed as a benefit for the auto sector in Canada which may be accelerated by the sector’s response to COVID 19. Indeed, the Minister in charge of Economic Development, Vic Fedeli most recently recognized this when he observed that if you link USMCA higher domestic content with the lessons learned on global supply chain resiliency as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, this “presents a great opportunity for our auto sector.”

Alan D. Bersin, Global Fellow, Mexico & Canada Institutes, Wilson Center; Former Assistant Secretary for International Affairs and Chief Diplomatic Officer for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Policy, Washington, DC

The USMCA calls for some enhancements in border management and trade facilitation. Should we expect lower wait times and border transaction costs once the agreement is implemented? If not, what is most needed to achieve that goal?

Chapter 7 of the USMCA (Customs Administration and Trade Facilitation), so far as it goes, makes a decidedly positive contribution and significantly improves the Customs Procedures Chapter of NAFTA, which it replaces, but it likely will not do the same for wait times and border transaction costs.

Chapter 7 embodies a terrific compendium (30 pages worth compared with 3 in its NAFTA predecessor) of the “gold standards and best practices” that have emerged over the past generation in the customs and border management world. It incorporates a number of significant features from the Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) of the World Trade Organization (derived from the Bali Accords) as well from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) to which Mexico and Canada have subscribed. These include provisions regarding the efficient release of goods (Article 7.7) as well measures calling for enhanced transparency, predictability and consistency (Article 7.11).

In addition, USMCA’s Chapter 7 not only expands (in Article 7.2) on previous NAFTA (section 1802) innovations, such as Online Publication, it also institutionalizes several key modes of operation introduced in the interim. These include the mandatory adoption of “information technology” and electronic processing (Article 7.9) and use of a coordinated “single window” (Article 7.10) by the three countries in due course. And then, most notably, Chapter 7 stakes out entirely new ground in areas as diverse as Express Shipments (Article 7.8), Standards of Conduct (Article 7.19) explicitly addressing corruption, and provisions to level the field between customs brokers and self-filers (Article 7.20). These are considerably bold provisions in what is typically a conventional and conservative multilateral context.

But none of the laudatory standards and best customs and practices highlighted in Chapter 7 (except possibly with respect to express shipments) are self-executing. Nor are there any resources identified, let alone allocated, to support the infrastructure requirements needed to implement the goals of reduced cross-border wait times and costs. In short, they will not happen absent the investment of both substantial human and financial capital in border management rather than (exclusively) in border security and control.

Nonetheless, Chapter 7 and USMCA have created a framework in which North American “ports of the future” could be designed, built, and operated by Canada, Mexico, and the United States in the event the political will and leadership to do so (somehow) materialized. Article 7.24, for example, creates a Committee on Trade Facilitation with a potentially robust agenda (Article 7.23) which recognizes the critical nature of Regional and Bilateral Cooperation on Enforcement (Article 7.26). Together these provisions could potentially produce bilateral and trilateral mechanisms to achieve much more efficient and effective border crossing results across North America.

So the short answer now to the opening question is: no. There will not be much material improvement in border efficiencies merely from the adoption of Chapter 7 and the implementation of USMCA. But the first rules of starting something new have been observed — namely, do no harm and create the conditions for change. At end, the economic success overall of the USMCA enterprise may generate the public support and resources, the private sector investment, and the inspired political leadership needed to convert Chapter 7 operationally into a routine state of affairs.

David Shirk, Global Fellow, Mexico Institute, Wilson Center; Professor & Graduate Director, Department of Political Science and International Relations, University of San Diego; Director, “Justice in Mexico” Project, San Diego, CA

The vast majority of U.S.-Mexico trade takes place at the land border. How do you expect the implementation of the USMCA to affect border communities and border economies?

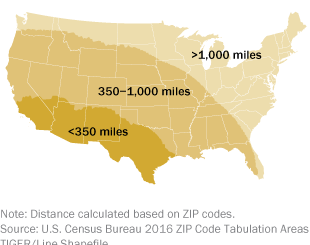

For me, as someone who lives along the southwest border, the most important impact of the revised NAFTA agreement is that there will be no major impacts. On the one hand, the “new” agreement basically retains the operational structure of NAFTA as we have known it for the past 30 years, with minor modifications to update the agreement and also build in some (relatively weak) protections for U.S. manufacturing. In this sense, there is not much “new” in the new agreement. The provisions of the renegotiated agreement will not fundamentally change the way commerce plays out across the border; they merely sustain the protocols that have been so successful at integrating the $1 trillion-plus North American trade zone. On the other hand, because the revised agreement does not significantly modify NAFTA, it also means that there are no new protocols to address long border wait times for people and goods that have accumulated over the past three decades, there are no new resources that have been allocated to improve infrastructure at ports of entry, and the agreement does not address the additional costs and negative externalities imposed on border communities by expanded trade. In short, there is relatively little value added in the new agreement, giving the lie to President Trump’s claim that NAFTA was the worst trade agreement of all time. This is why the president did not follow through on his dubious threats to withdraw from NAFTA, and pressed hard to come up with something that he could brand as his own. Indeed, any honest assessment of the ineptly-named “USMCA” will recognize that the best thing about the new agreement is that it is simply NAFTA 2.0 (or 1.1). To be sure, the new agreement introduces new “Rules of Origin” to increase North American content, raises wages to $16/hour in the 40-45% of exports in the automotive sector, and lowers barriers on financial services, telecommunications, and data services. Yet, these are only marginal improvements, some of which would have been included in the TPP, which Trump scrapped.

In this sense, the Trump administration clearly wasted a historic opportunity to fundamentally rethink North American relations in a way that will ultimately increase and facilitate cross-border flows of people, capital, and goods. Over the long term, all three countries will need to seriously evaluate the prospects for NAFTA 3.0. Such an agreement would address some of the real challenges the three countries now face along the border, including crumbling and inefficient trade infrastructure, cumbersome policies for the movement of labor, subpar labor and environmental standards (in both Mexico and the United States), and continued uncertainty for international investors due to sharp differences in the legal landscapes across the three countries. In the meantime, USMCA poses as a placeholder for the North American partnership we all deserve.

Agustín Escobar Latapí, Global Fellow, Mexico Institute, Wilson Center; Professor, CIESAS Occidente, Guadalajara, Mexico

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought a new focus to issues of supply chain management and resilience. With its new labor dispute mechanism and other provisions, should we expect issues of supply chain integrity to gain new prominence as well?

A labor dispute mechanism existed in NAFTA, and it was resorted to by each country.

However, in USMCA, the dispute mechanism has been upgraded. Labor inspection can take place much more freely in connection with real or apparent labor violations. Mexico had in fact relied on low-cost, high-skill labor to better compete in NAFTA, and significant stakeholders in Mexico and elsewhere pushed for improvements in labor conditions. In USMCA, there is a pressing need to upgrade labor conditions in Mexico especially. In principle, therefore, I view the labor dispute mechanism in USMCA positively. It should help work conditions converge. All employers, and Mexicans in particular, should be concerned that conditions for their workers meet USMCA standards, but also that workers are safe and well cared for. The price for not doing so is suffering regional supply network disruptions.

Supply chain resilience is being developed. Integrated manufacturing is taking place once again. The expertise to prevent and minimize infections, and to mitigate and adapt to their consequences, is being tried. I foresee a period of at least three years during which incomplete or unsuccessful vaccines, widely differing firm and country strategies, and variations in leadership, will hurt people and supply chains. My wish is for a proposal that involves a common North American comprehensive strategy, including protocols, the best vaccines available, and supply chain alternatives within North America. We have not handled the pandemic successfully. We urgently need a joint, successful strategy to deal with it in supply chains, and to strengthen the position of North American manufacturing and innovation in geopolitical terms.