Statistics show region not violent as officials say

by Brian M. Rosenthal and Mark Collette, Houston Chronicle

Much of the narrative that Texas officials have used to justify their surge of state police and National Guard troops to the southern border has been wrong, according to the first comprehensive look at state crime statistics since it began.

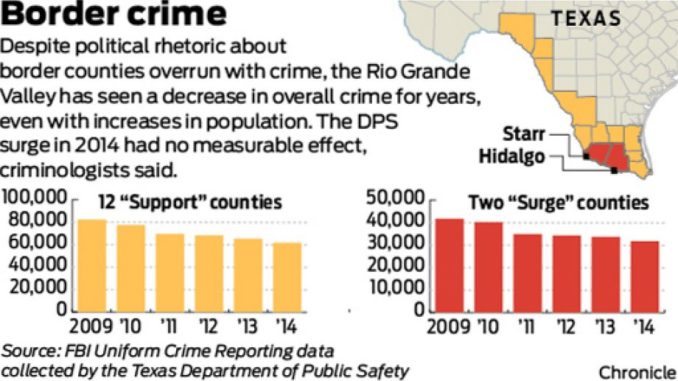

Politicians paint the region as overrun by gangs and drug cartels, but the numbers indicate that when officials ordered the surge, the rate of serious crime in the Rio Grande Valley was at its lowest level in years. And in the 11 months since, the rate has not been significantly affected by the extra manpower.

Instead, according to the Houston Chronicle analysis of tens of thousands of pages of data compiled by the state as well as 911 call logs of individual police departments, South Texas has been experiencing a steady crime reduction in line with what has been taking place across the country since the 1990s.

The Texas Department of Public Safety disputed the analysis, saying it failed to account for organized crime and how smugglers affect lives beyond the border region. DPS spokesman Tom Vinger and other officials also said the surge was meant to combat the smuggling of people and drugs across the border, not fight local crime.

The promise of fighting crime, however, was a big part of how the surge was sold to the public.

Last June, when then-Gov. Rick Perry and other state leaders ordered more police to the border, they said, “various crimes directly related to cartels – murder, sexual assault, extortion, child prostitution, home invasion – put Texas citizens’ lives at risk and strain the resources of state and local law enforcement and criminal justice systems.”

The next month, Perry announced the guard deployment by saying he would not “stand idly by while our citizens are under assault,” then scoffed when the first question came from a reporter who cited the mayors of McAllen and El Paso to challenge the idea that crime was soaring.

The former governor, who is expected to announce a second presidential bid next month, declined comment for this story. So did current Gov. Greg Abbott, Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick and the chairmen of committees in both chambers overseeing border security.

‘Bring consistency’

House Speaker Joe Straus responded to comment request by touting that chamber’s border-security proposal, saying in a statement that House Bill 11 would “bring consistency to our border security strategy, reducing the need for occasional surges.”

“The House will monitor this issue closely over the next two years and fully evaluate our approach in the next legislative session,” he added. The release of data follows months of resistance to Chronicle public records requests. It comes as lawmakers are close to approving a two-year budget that would put $800 million more into border security at the urging of Abbott and Patrick.

The statistics also inject hard numbers into a debate that has been raging since a spike in unaccompanied children crossing the border captivated public attention last spring. The spike started subsiding before the surge and continued to trend downward, leading Republicans and Democrats to argue about the role the extra troops played.

DPS response to border surge data

DPS response to border surge data

Republicans also have said the surge was needed to combat crime brought by foreign gangs and drugs, while Democrats have questioned the value of the more than $100 million price tag for a region they described as safe.

State officials have largely used anecdotes to illustrate how the surge has succeeded in combating organized crime. A classified report to lawmakers obtained by the Chronicle in February listed examples of encounters with cartel members, immigrant “stash houses” and more, but it lacked detailed data.

The numbers DPS has released have mixed state efforts with federal and local law enforcement and concerned illegal immigrant apprehensions, drug seizures and interactions with gang members, which do not speak to overall crime rates.

The Chronicle analysis used five years of data reported to the state under Uniform Crime Reporting, a decades-old program run by the FBI. Absent newer data collection that Texas has yet to adopt, UCR is considered a good indicator of overall crime.

The newspaper focused on Hidalgo and Starr counties, the primary area of operations for the surge, known as Operation Strong Safety. It also looked at crime in a 12-county region from Brownsville to Del Rio, where less-intensive support operations have been conducted.

Vinger, the DPS spokesman, said any complete analysis would look even farther, because criminals who cross the border usually penetrate deeper into America.

“If any community in our country has a drug problem, they most likely have a cartel and unsecure border problem,” he said.

Abbott has agreed and has called for more funding for anti-gang efforts across the state because of the lack of border security.

New reporting systems

Vinger also noted the UCR data don’t account for “crimes committed and threats posed by modern-day criminal enterprise organizations” in Texas, including drug smuggling, extortion, money laundering and kidnapping.

DPS has urged lawmakers to authorize new reporting systems that would take these into account, and the soon-to-be-approved plan would do that.

Former Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst, who helped push the surge, agreed it was wrong to analyze crime using the “antiquated” UCR.

“We were right to fund the law enforcement surge then and I’d do it again,” Dewhurst said in a statement.

But the analysis of the 911 call logs included some categories of crime not in the UCR data and showed similar downward patterns. For example, there were a combined 23 calls about possible kidnappings to the Brownsville, Edinburg, Harlingen and McAllen police departments and Hidalgo and Zapata county sheriff’s offices in the first half of 2014 – less than in the first half of 2013 (31) or 2012 (25).

Overall, the UCR data showed that Hidalgo and Starr counties reported 31,815 “type 1” crimes in 2014, which include homicide, aggravated and sexual assault, burglary and robbery, and auto theft. That was down from 41,730 in 2009.

In the broader, 12-county region, reported crimes dropped from 82,277 in 2009 to 61,720 in 2014.

“There was no indication in the 911 call logs that the crime drop occurred any faster or slower after the surge.

Several criminologists noted the drop happened even as the Valley’s population increased and even during an influx of tens of thousands of immigrants during the summer of 2014. That means the crime rate – the number of crimes per capita – dropped even faster than the number of crimes.

There were two notable exceptions in the data for Hidalgo County: Sexual assaults increased from 197 in 2013 to 362 in 2014, the highest in at least five years, and aggravated assaults rose from 1,658 to 1,906. But the rates per capita remained comparable to or below those of major metro areas in Texas, and the exceptions were most likely normal fluctuations, said Rob Guerette, a transnational crime expert and professor at Florida International University.

“There doesn’t appear to be anything extremely abnormal, certainly not to the extent that would justify the expenditure of resources and energy that was put out,” Guerette said.

Ramiro Martinez, a professor of sociology and criminal justice at Northeastern University in Boston, agreed the numbers show that violent crimes such as robbery are declining on the border.

“If anyone makes a contrary claim, they need to prove it with strong facts or data, not fiction or rhetoric,” Martinez said.

The Department of Public Safety for months has faced complaints about its reluctance to release data, particularly from Democratic lawmakers.

The Chronicle encountered several delays in trying to get numbers. The newspaper first requested the UCR data in July under the Texas Public Information Act, going directly to the state because at that point the statistics had not yet been sent to the FBI. The release came only after repeated inquiries by the Texas Attorney General’s Office to DPS.

“DPS has been unwilling to release this information, and now we know why,” said state Rep. Armando Walle, D-Houston. “These numbers show that what our Republican leaders have been telling us has not been true.”

It ‘got out of whack’

Hidalgo County Judge Ramon Garcia agreed, noting he and others have been saying for months that the narrative about increasing crime put forward by state officials has been wrong.

Garcia blamed Perry, who he said wanted to deploy the National Guard for political reasons.

“You had a governor who is running for president and needed an issue and chose border security,” he said. “That’s how this whole thing got out of whack.”