By Ronald Brownstein, National Journal

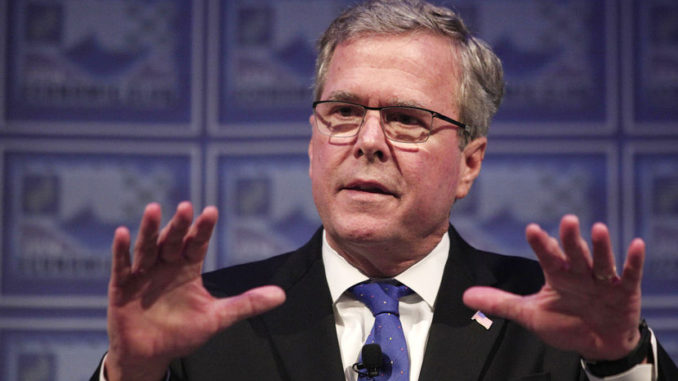

Jeb Bush has committed himself to testing a critical question that each of the GOP’s past two presidential nominees would not: whether support for comprehensive immigration reform that includes a pathway to citizenship is a poison pill in the GOP primary.

In the process, Bush is forcing a debate that will gauge how much the party’s current coalition is willing to change its agenda to court new voters.

Though congressional Republicans have shelved discussion of immigration reform, Bush’s recent indication that he still supports a pathway to citizenship for some of the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants guarantees that the GOP will confront the issue more directly in its upcoming presidential race than in 2008 or 2012. The coming skirmishes will likely determine whether the eventual GOP nominee can reconsider hard-line party positions on immigration that have alienated the growing Hispanic population that is now central to the modern Democratic coalition.

While John McCain and Mitt Romney, the eventual nominees in the 2008 and 2012 contests, earlier indicated support for citizenship to varying degrees, each man backed away from that position during his race. Bush made a very different calculation earlier this month in New Hampshire when he reasserted that he would support a pathway to citizenship for the undocumented, so long as it imposed demanding conditions and was embedded in comprehensive immigration-reform legislation that included tougher security.

Since signaling his interest in the 2016 race, Bush had previously spoken in more ambiguous terms about supporting “legal status”—possibly something short of full citizenship—for the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants. Bush had vacillated between those two positions as well around the release of the 2013 book he co-authored on immigration reform, Immigration Wars.

But in New Hampshire, Bush explicitly declared that he would support citizenship if Congress approved it as part of a larger immigration package that required the undocumented to pay fines, learn English, and pass other hurdles. Citing the 2013 Senate legislation crafted by the bipartisan Gang of Eight that provided a pathway to citizenship, Bush insisted: “If you could get a consensus done where you could have a bill done, and it was 15 years [for citizenship] as the Senate Gang of Eight did, I would be supportive of that.”

Bush has joined the other likely GOP contenders in pledging to revoke President Obama’s proposed executive action that would provide legal status, but not citizenship, to about 5 million undocumented immigrants. But by indicating he would support a legislated path to citizenship, Bush decisively separated himself from potential 2016 rivals like Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and Florida Sen. Marco Rubio—each of whom has moved away from earlier support for citizenship. (Rubio was a principal author of the 2013 bill.) Bush also made a very different calculation than either McCain or Romney.

Before his 2008 presidential bid, McCain joined with Democratic Sen. Ted Kennedy to drive through the Senate comprehensive immigration legislation similar to the 2013 bill that included a pathway to citizenship, along with a guest-worker program and tougher enforcement. As Massachusetts governor, Romney did not fully endorse the McCain-Kennedy legislation, but he described it as “reasonable” and rejected the charge that it represented amnesty for the undocumented.

But by the time of the 2008 GOP presidential primaries, both men had distanced themselves from the legislation. Reversing his earlier view, Romney denounced the McCain-Kennedy bill as amnesty and touted hard-line positions against undocumented immigrants.

Even McCain wavered after the Republican-controlled House refused to consider his legislation amid a conservative backlash. Through the 2008 GOP primaries, the Arizona senator moved away from the bill and said as president he would instead pursue the approach favored by conservatives: working first to further secure the border before considering any change in status for the undocumented. In a January 2008 debate, McCain reached the deepest point of his retreat when he said that he would not vote for his own legislation if it reached the floor again. “No, I would not, because we know what the situation is today,” he said. “The people want the border secured first.”

When Romney ran again in 2012, he moved still further right on immigration. He denounced Texas Gov. Rick Perry for backing in-state tuition for the children of undocumented immigrants and pledged to tighten enforcement to a level that encouraged immigrants here illegally to pursue “self-deportation.” Though former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, one of Romney’s chief rivals, insisted that the country would not deport millions of families, no major candidate made the case for providing citizenship to those here illegally.

Though George W. Bush won the GOP nomination in 2000 while broadly supporting immigration reform, the past two races have hardened the assumption among many Republican operatives that support for legalizing the undocumented—which conservatives deride as “amnesty”—is an unsustainable position in the GOP primary.

But the polling evidence isn’t so clear-cut. While surveys show that citizenship faces an impassioned streak of resistance among likely Republican voters, the polls offer mixed signals on whether enough voters remain open to a candidate holding that position to build a winning coalition.

The most ominous result for Bush came in the most recent NBC/Wall Street Journal Poll. In that survey, 62 percent of Republican primary voters said they would be less favorable toward a candidate “who supports a pathway to citizenship for foreigners who are currently staying illegally in the United States,” while only 22 percent indicated they would be more favorable. The share of GOP voters who said they would be less favorable toward a candidate supporting citizenship exceeded the portion who indicated resistance to a candidate favoring Common Core curriculum reform (52 percent), raising taxes on the wealthy (51 percent), or same-sex marriage (50 percent).

Douglas Holtz-Eakin, McCain’s issue director in 2008 and now president of the American Action Forum, a center-right think tank, says that because of its phrasing, that result overstates GOP voter opposition to citizenship. “It’s too simple, because when you just ask it that way, people skip over the pathway [language] and they just think ‘citizenship-amnesty-bad,’” he said. “That’s the trap.”

A series of surveys in recent years have found that most Republicans reject deportation and are willing to accept some legal status for the undocumented—but only a minority of them endorse full citizenship.

Polling conducted by longtime GOP pollster Whit Ayres for AAF last year found that a 56 percent to 36 percent majority of likely GOP primary voters would accept a legal status “that does not provide full citizenship.” But by a 48 percent to 44 percent plurality, GOP primary voters rejected citizenship, the survey found. Polls by the nonpartisan Pew Research Center during the 2013 immigration debate likewise found that, while a solid majority of about three-fifths of Republicans believed the undocumented should be allowed to legally remain in the United States, only about one-third of GOP partisans endorsed citizenship.

Exit polls in Arizona and Florida during the 2012 GOP primaries produced comparable results. In each case, about one-third of GOP voters supported citizenship for the undocumented and roughly another fourth said they should be provided legal status short of full citizenship; about one-third said they should be deported (with the remainder uncertain). Similarly, in the exit poll conducted by Edison Research among voters in the 2012 general election, Republicans backed some legal status over deportation by 51 percent to 42 percent.

More recent evidence, though, suggests Obama’s move to provide legal status for many of the undocumented may have hardened Republican attitudes. In the 2014 election national exit poll, 57 percent of Republican voters said the undocumented should be deported, while only 38 percent backed legal status.

One other recent piece of evidence completes the picture. In February, the NBC/Marist Poll asked likely GOP primary voters in three crucial early states whether a candidate who supported immigration reform “including a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants” would be acceptable to them. Likely Republican primary voters in Iowa split exactly in half, with 49 percent saying yes and 49 percent no. In New Hampshire, 43 percent said yes and 54 percent no. In South Carolina, 46 percent said yes and 52 percent no. The share that described a candidate supporting a pathway to citizenship as “totally unacceptable” was smaller, ranging from 27 percent to 33 percent across the three states.

Like these other polls, those results clearly indicate substantial resistance in the GOP electorate to a candidate supporting citizenship. But they also suggest that a candidate backing citizenship can still compete for a critical mass of voters who do not consider it disqualifying. Even some voters who term the issue disqualifying might not act that way in practice, notes Hogan Gidley, a former executive director of the South Carolina Republican Party who worked for Rick Santorum in 2012 and will advise Mike Huckabee this time. “I was executive director when Sen. Lindsey Graham got booed at our convention because he said he was for immigration reform,” Gidley said. “And then he absolutely won in a landslide in this state for reelection. I wouldn’t say it’s a disqualifier.”

For Bush, the challenge of defending support for citizenship is compounded because he also has reaffirmed his embrace of the Common Core curriculum reforms that further alienate many conservatives. (Gidley believes Common Core may ultimately prove a larger hurdle for Bush than immigration.) Those positions may help explain one of the most striking results in the recent national NBC/Wall Street Journal survey: In that poll, fully 45 percent of Republicans who identified as conservative said they could not see themselves supporting Bush for the nomination. That was much more than the 33 percent of moderates or liberals who felt that way about Bush, or the share of conservatives who said they could not back potential rivals Walker (15 percent) or Rubio (23 percent).

Taken together, all these results suggest that, while Bush’s position on immigration (and Common Core) is probably not an insurmountable hurdle, it will narrow the range of Republican voters he can realistically compete for. To win the nomination, he will need to heavily consolidate the party’s most centrist and slightly right-of-center elements against what these polls suggest could be formidable resistance from the conservative ideological vanguard.

McCain and Romney won the nomination despite facing a similar equation. But each man beat opponents—Huckabee and Santorum—who never expanded their support much beyond evangelical conservatives. Bush could face a more strenuous test if the early primaries elevate an alternative such as Walker or Rubio. Both men have moved to defuse conservative opposition by conceding on immigration reform, and polls suggest either could appeal broadly across the party—though both might also find their own reach narrowed as the debate develops. “This nomination will be won by the candidate who can unite the various factions of the party,” argues Ayres, who is backing Rubio. “They may not be the first choice or even the second choice of each individual faction, but they will be acceptable to all factions.”