Modernizing ports of entry at the southern border has gained prominence as dramatic increases in immigration have stretched border security personnel and the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted supply chains, driving more manufacturing to North America.

by Reyes Mata/El Paso Inc.

Amid a chaotic flow of migrants to the southern border, the United States and Mexico are pushing forward with an aggressive investment into the international ports of entry along the nearly 2,000 miles of their shared boundary.

The southern border – a complex network of more than 44 active ports that facilitate the world’s largest number of international crossings – has a massive impact on both nations’ economies.

With trade between the two countries exceeding $1 million each minute, July 2022 alone saw “more than $53 billion crossing the southern border via trucks and trains,” according to a 2022 nonpartisan study by The Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

As industries emerge from the crippling effects of the eight-month COVID-19 shutdown of the border, border experts are encouraged by the steps taken by both federal governments to invest in international ports of entry.

“It’s a big deal,” said John McNeece, senior fellow for energy and trade at the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies at the University of San Diego. “The bipartisan infrastructure law puts big dollars into land ports of entry, and that’s public investment, so it’s a good thing. I’m very happy they’re doing that.”

At the 2023 North American Leaders’ Summit in Mexico City earlier this year, U.S. President Joe Biden and Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador pledged to invigorate the trade sector between the two countries. Utilizing the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure package, the U.S. has pledged $3.4 billion “to construct, acquire, repair and alter” 26 land ports of entry – 20 at the Canadian border and six at the southern border.

Mexico has pledged $1.5 billion between 2022 and 2024.

Modernizing ports of entry at the southern border has gained prominence as dramatic increases in immigration have stretched border security personnel and the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted supply chains, driving more manufacturing to North America.

In a recent visit to El Paso, U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg told El Paso Inc. that southern land ports, including the high-trade corridor of the El Paso region, are on the priority list for infrastructure funding.

“That’s part of why we’re here – to make it clear that we see this community and we see its needs. It’s very much on our mind as we look at the next rounds of grants coming up,” he said. “When you look at the infrastructure bill and the funding that is there, one of the pieces that is least appreciated, except in border communities, is the funding for land ports of entry.”

A February 2023 analysis by the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center, the University of Texas at El Paso’s Hunt Institute for Global Competitiveness, and El Colegio de la Frontera Norte found that decreasing wait times at the border by even 10 minutes would mean a boost in trade dollars.

“This reduction would allow for an additional $25.9 million worth of goods to enter the United States every month and lead to $547,000 in extra spending across the United States’ four border states,” the report stated.

One land port in California will receive modernization funding through the federal infrastructure package, as will three in Arizona.

Two ports in Texas will receive funding – the Bridge of the Americas port of entry in El Paso and the Brownsville-Gateway port of entry in Brownsville.

The Bridge of the Americas – known in the region as the “puente libre,” or the “free bridge,” because it has no crossing tolls – will receive between $650 million and $700 million for “new facilities for administration and improved facilities for pedestrian, passenger, commercial and primary inspections,” according to the U.S. General Services Administration.

The 28-acre port of entry, which is one of four international bridges in El Paso, was built in 1967 and handles an average of 600 commercial vehicle crossings daily, 12,500 passenger cars and trucks, and 2,500 pedestrians, according to the GSA.

“The presidents of the U.S. and Mexico and the prime minister of Canada are all trying to foster good relations, including trade, and I’m very strongly in favor of that process and just want them to keep talking,” said McNeece. “So the question is, how is that going to be deployed?”

How successfully the federal funding from both countries is invested in the ports of entry is top of mind for many observers.

Historically, communication between the two countries has been problematic in the construction of ports of entry. There are a myriad of local, state and federal agencies on both sides of the border requiring a range of protocols for constructing and renovating the ports.

Earl Anthony Wayne, a distinguished diplomat in residence at the American University School of International Service in Washington, D.C., said that binational communication for port of entry construction has been inconsistent.

“I think it’s fair to say that it wasn’t sufficient on a consistent basis in the past, and it needs to be better as we go forward,” he said. “We have to make sure that what happens is that they actually coordinate and talk to each other and come up with compatible planning.

“The new projects should be models for more efficient planning and coordinated implementation as we go forward, because it is a significant amount of money pledged. You want good results, and you want results as quickly as you can get them because there’s this dire need for more modern infrastructure at many places along the border.”

Wayne said an example of botched binational planning occurred at a California-Baja California port of entry.

“On the Tijuana-San Diego border, there was a lot of back and forth where the U.S. and Mexico built the feeder roads that came together two miles separate from each other,” he said.

A decade ago, El Paso experienced similar difficulties.

“The story that has reached the status of North American lore is the tale of the Tornillo-Guadalupe port of entry, outside of El Paso,” Kimberly Breier with the Center for Strategic and International Studies wrote in a 2017 analysis. “For many years the crossing was known as the ‘bridge to nowhere,’ as construction on the U.S. side of the entry was begun in 2011 and completed two years later with a bridge that literally stopped at the border with Mexico.”

The U.S. spent $133 million to complete the U.S. portion of the port in 2013, but construction stalled on the Mexican side. Former El Paso County Commissioner Vince Perez said at the time that “this project reflects the challenges there are in constructing port of entries.”

“It’s probably one of the most complex construction projects there is,” he told reporters. “If you were to see the site, you would see the bridge hanging halfway.”

The Tornillo-Guadalupe port of entry was eventually completed in February of 2016.

Andrew Rudman, director of the Mexico Institute at the Wilson Center, a think tank in Washington, said staffing is also a problem, and increased migration could diminish the intended economic impact of modernizing the ports.

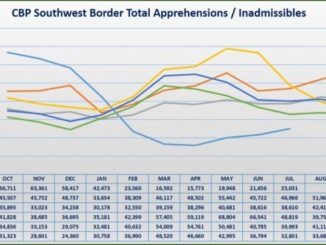

“This is in part because you have a finite number of border protection and customs officers, so the more of them that are diverted to the smuggling of people and people crossing the border, then the less people are available to manage commerce,” he said.

Also complicating the stability and profitability of trade – and political tension – between the U.S. and Mexico was the precedent set when the U.S. threatened to close the border in 2019, a move that connected the flow of commercial goods with the flow of immigration from Mexico.

“Historically we’ve kept immigration and trade as entirely separate issues. But that of course all changed with the Trump administration,” said Duncan Wood, a vice president at the Wilson Center. “The Trump administration decided that they would explicitly link immigration and trade when they threatened Mexico with a border closure unless Mexico did more to stop the flow of Central Americans north.

“They basically gave the Mexicans a bargaining chip so that from that point on, every time there’s pressure on the Mexicans from the U.S. side, on whatever issue, they say, ‘Well, do you still want us to help you out with migration?’ So that issue linkage has become a reality of the relationship, particularly under Lopez Obrador.”

Other plans are also underway for the El Paso region.

The Texas-Mexico Border Transportation Master Plan was adopted by the Texas Transportation Commission in 2021. A long-range plan for the border region, it identifies challenges and strategies for improving the crossings of goods and people.

It focuses on three regional master plans, including one for this region, encompassing El Paso, Santa Teresa and Chihuahua.

BTMP initiatives do not receive funding from the federal infrastructure law. The U.S. funding comes primarily through “budget appropriations to GSA and CBP” and through “third parties such as the state of Texas, counties, cities and the private sector.” In Mexico, most of the funding comes through the Instituto de Administración y Avalúos de Bienes Nacionales, according to its report.

Lauren Macias-Cervantes, a public information officer at TxDOT, referred media inquiries to the BTMP report, which states that this region “obtained $44.6 million in investments for border crossing infrastructure from 1994-2019.”

According to the report, the region’s needs include enhancing its capacity to handle hazardous materials, improving the infrastructure of pedestrian and bike routes “particularly at border crossings and connecting roads,” and improving the design of streets “to enable safe use and support mobility for all users.”

It also identified the need to improve bridge conditions that are “structurally deficient or functionally obsolete” in the Downtown El Paso area.

Rudman, with the Wilson Center, said the billions of dollars of funding for ports of entry along the Southern border is a good indication that the highest levels of government recognize the critical role of the border and its ability to generate income while handling unprecedented migration numbers.

This is particularly true, he said, because Title 42 – the public health policy that has allowed the U.S. to quickly turn migrants away at the border – is set to be lifted May 11. Any disarray at the border that may result, and any interruption of trade, may affect the approaching U.S. presidential election, Rudman said.

“Certainly, in the U.S., the migration issue is going to be in the 2024 campaign,” he said. “How it plays out when Title 42 is lifted will definitely have an impact on the campaign. It will be up to the voters to decide how they see it.”

.

This story was produced with the support of the Puente News Collaborative, a binational partnership of news organizations in Juárez and El Paso.