The underlying economic forces widening this political divide will be difficult for either side to reverse. The places benefiting from the new opportunities in information-based industries, tend to be racially diverse, densely populated, well educated, supported by prestigious institutions of higher education, and tolerant of diverse lifestyles.

by Ronald Brownstein, The Atlantic

In red and blue states, Democrats are consolidating their hold on the most economically productive places.

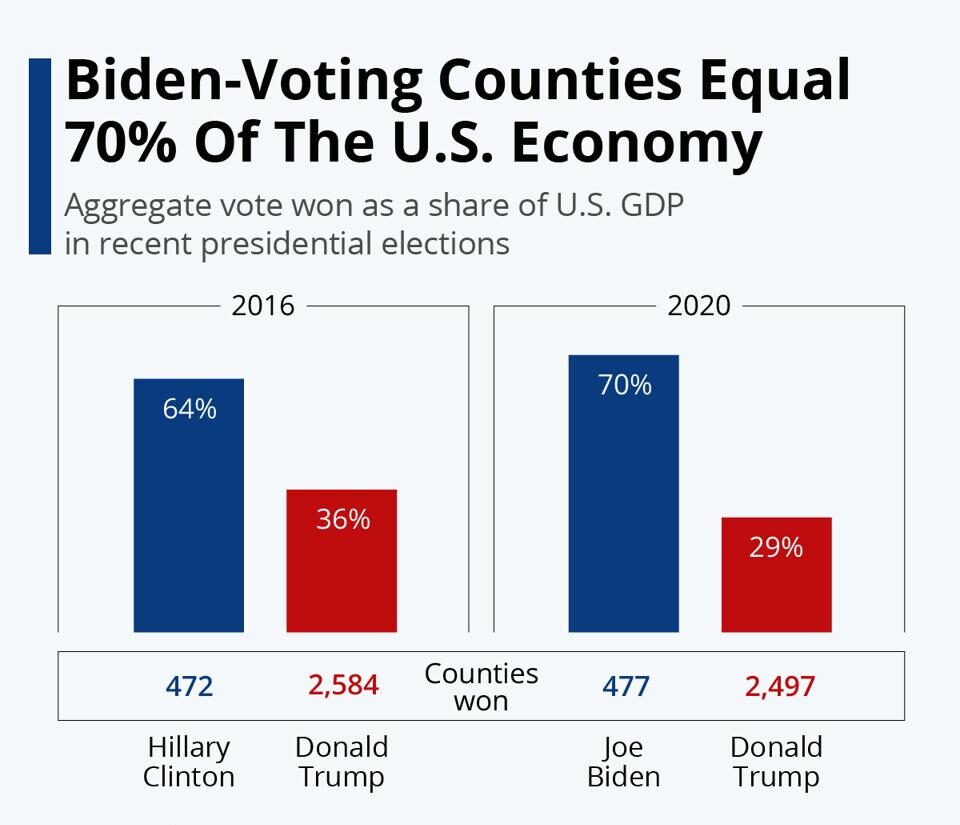

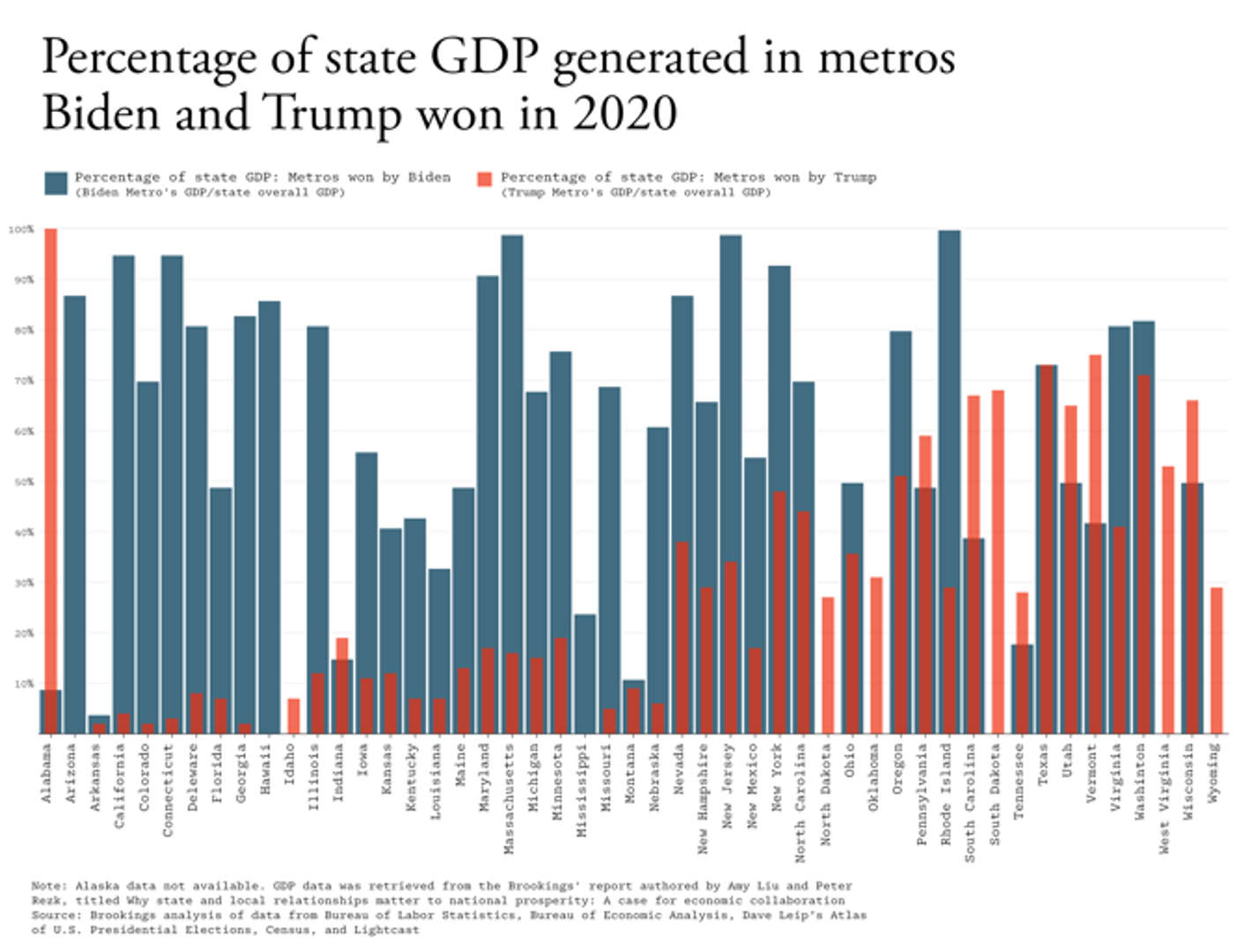

Metropolitan areas won by President Joe Biden in 2020 generated more of the total economic output than metros won by Donald Trump in 35 of the 50 states, according to new research by Brookings Metro provided exclusively to The Atlantic. Biden-won metros contributed the most to the GDP not only in all 25 states that he carried but also in 10 states won by Trump, including Texas, Missouri, Nebraska, Iowa, Utah, Ohio, and even Florida, Brookings found. Almost all of the states in which Trump-won metros accounted for the most economic output rank in the bottom half of all states for the total amount of national GDP produced within their borders.

Biden’s dominance was pronounced in the highest-output metro areas. Biden won 43 of the 50 metros, regardless of what state they were in, that generated the absolute most economic output; remarkably, he won every metro area that ranked No. 1 through 24 on that list of the most-productive places.

The Democrats’ ascendance in the most-prosperous metropolitan regions underscores how geographic and economic dynamics now reinforce the fundamental fault line in American politics between the people and places most comfortable with how the U.S. is changing and those who feel alienated or marginalized by those changes.

Just as Democrats now perform best among the voters most accepting of the demographic and cultural currents remaking 21st-century America, they have established a decisive advantage in diverse, well-educated metropolitan areas. Those places have become the locus of the emerging information economy in industries such as computing, communications, and advanced biotechnology.

And just as Republicans have relied primarily on the voters who feel most alienated and threatened by cultural and demographic change, their party has grown stronger in preponderantly white, blue-collar, midsize and smaller metro areas, as well as rural communities. Those are all places that generally have shared little in the transition to the information economy and remain much more reliant on the powerhouse industries of the 20th century: agriculture, fossil-fuel extraction, and manufacturing.

Neither party is entirely comfortable with this stark new political alignment. Much of Biden’s economic agenda, with its emphasis on creating jobs that do not require a college degree, is centered on courting working-class voters by channeling more investment and employment to communities that feel excluded from the information age’s opportunities. And some Republican strategists continue to worry about the party’s eroding position in the economically innovative white-collar suburbs of major metropolitan areas.

Yet the underlying economic forces widening this political divide will be difficult for either side to reverse, Mark Muro, a senior fellow at Brookings Metro, told me. The places benefiting from the new opportunities in information-based industries, he said, tend to be racially diverse, densely populated, well educated, cosmopolitan, supported by prestigious institutions of higher education, and tolerant of diverse lifestyles. And the information age’s tendency to concentrate its benefits in a relatively small circle of “superstar cities” that fit that profile has hardly peaked. From 2010 to 2020, Muro said, the share of the nation’s total economic output generated by the 50 most-productive metropolitan areas increased from 62 to 64 percent, a significant jump in such a short span. “We are still in the midst of that massive shift, though there’s plenty of uncertainty right now,” Muro told me. “These are long cycles of economic history.”

The trajectory is toward greater conflict between the diverse, big places that have transitioned the furthest toward the information-age economy and the usually less diverse and smaller places that have not. Across GOP-controlled states, Republicans are using statewide power rooted in their dominance of nonmetropolitan areas to pass an aggressive agenda preempting authority from their largest cities across a wide range of issues and imposing cultural values largely rejected in those big cities; several are also now targeting public universities with laws banning diversity, equity, and inclusion programs and proposals to eliminate tenure for professors.

This sweeping offensive is especially striking because, as the Brookings data show, even many red states now rely on blue-leaning metro areas as their principal drivers of economic growth. Texas, for instance, is one of the places where Republicans are pursuing the most aggressive preemption agenda, but the metros won by Biden there in 2020 account for nearly three-fourths of the state’s total economic output.

“State antagonism toward cities is not sustainable,” says Amy Liu, the interim president of the Brookings Institution. “By handicapping local problem solving or attacking local institutions and employers, state lawmakers are undermining the very actors they need to build a thriving regional economy.”

At The Atlantic’s request, Muro and the senior research assistant Yang You of the Brookings Metro program calculated the share of state GDP generated across the 50 states in the metropolitan areas won by Biden and Trump in 2020. (The calculation was based on 2020 data from the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis. In federal statistics, 46 metropolitan areas extend across state lines—for instance, the New York metropolitan area also includes parts of New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Brookings disaggregated the economic and political results along state boundaries to ensure that each was apportioned to the correct total.)

The analysis showed that the metros Biden carried generated 50 percent or more of state economic output in 28 states, and a plurality of state output in seven others. States where Biden-won metros accounted for the highest share of economic output included reliably blue states: His metros generated at least 90 percent of state economic output in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Jersey, California, Connecticut, New York, and Maryland. But the Biden-won metros also generated at least 80 percent of the total economic output in Arizona, Nevada, and Georgia, as well as two-thirds in Michigan and almost exactly half in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania—all key swing states. And the metros he carried generated at least half of total output in several Republican states, including Texas, Iowa, and Missouri.

The metropolitan areas Trump carried accounted for the most economic output in only 15 states. Twelve of the states where Trump metros accounted for the most economic activity ranked in the bottom half of all states for total output; the only exceptions were Indiana, Tennessee, and Louisiana. By contrast, Biden dominated the most productive states: His metros generated more of the output than the Trump metros in 22 of the 25 highest-producing states. As striking: Biden metros generated at least half of total output in 12 of the 15 most productive states and 19 of the top 25.

All of these results reflect the emphatic blue tilt of the largest and most economically productive metro areas. In 37 states, Biden won the single metro that generated the largest economic output. The results in the 50 metros that contributed the most to the national GDP regardless of their state were even more decisive: Biden, as noted above, not only carried 43 of them—and won the two dozen largest—but carried more of the highest-performing metros in red states than Trump did. The list of high-performing red-state metro areas that Biden carried included all four of the largest in Texas—Houston, Dallas, Austin, and San Antonio.

“The states that are most invested in the knowledge economy are overwhelmingly Democratic; large metros [in almost every state] are essentially universally Democratic; and affluent voters in these large metro areas are now overwhelmingly Democratic too,” Jacob Hacker, a Yale political scientist, told me. “The basic story seems to be that where you are seeing rapid economic growth, where the nation’s GDP is produced, you are seeing an ongoing shift toward the Democratic Party.”

Biden also won 28 of the next 50 metros that generated the most economic output, giving him 71 of the 100 largest overall, Brookings found. After the top 100, the switch flipped: Trump won 62 of the next 100 metros ranked by their total output, and 143 of the final 184 metros with the smallest economic output.

To understand these patterns better, the Brookings Metro analysis took an especially close look at the demographic and economic characteristics of metro areas in eight of the most politically competitive states, as well as the two mega-states in each party’s column: California and New York for the Democrats, and Texas and Florida for the Republicans.

Those results fill in the picture of a broad-based separation between the Democratic- and Republican-leaning places. Across those 12 states, Biden won about three-fifths of the metros with a population of at least 250,000; Trump won about three-fourths of those that are smaller. In these states, Biden won about three-fourths of the metros with more college graduates than average and Trump won about two-thirds of those with fewer college grads than average. Biden likewise won almost two-thirds of these states’ metros that are more racially diverse than average, and Trump won two-thirds of those that are less diverse. Biden predominated in the metros with the largest share of workers participating in digital industries, and Trump won 17 of the 20 metros with the largest share of workers engaged in manufacturing.

Despite their economic success, many of the largest blue-leaning metros, especially since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, have faced undeniable turbulence in the form of high housing costs, widespread homelessness, persistent economic inequality, downtown business centers weakened by the rise of remote work, and, in many cases, increasing crime. Some of the very largest metros “may be seeing new headwinds,” Muro said, but if employers look beyond them, the beneficiaries are less likely to be the smaller Trump-leaning places than the blue cities just outside the highest rung of economic activity, such as Denver, Atlanta, and Phoenix. Brookings’s analysis has found that even amid all of the pandemic’s disruption, the elevated share of total national economic output generated by the 50 largest metros remained constant from 2019 through 2021. Though trends can always change, Muro said, “it is hard to imagine a massive unrolling” of the concentration of economic opportunity that has characterized the digital era.

Lower taxes and especially less-expensive housing costs have helped many red-state metros remain competitive with those in blue states as the economy evolves, but a sustained conservative attack on red states’ most prosperous places could threaten that record. “The biggest worry is that the culture wars, the attack on the urban core, the attack on the self-governing of cities can have the unintended effect of pitting urban areas against their suburbs and rural neighbors when the modern economy is regional and we need all of these actors to work together,” Amy Liu of Brookings said.

This economic configuration has big implications for national politics. Hacker believes that over time, ceding so much ground in the most economically vibrant places “is not a sustainable position for the Republican Party to be in.” While the party is “benefiting from the undertow” of backlash against the overlapping economic and social transformations reconfiguring U.S. society, he added, “the places that are becoming bluer are growing faster; they are bigger … and they are also, as Republicans lament, setting the tone” for the emphasis on diversity and cultural liberalism now embraced by most big public and private institutions.

Still, Hacker noted, the GOP’s “structural advantages” in the electoral system—particularly the bias in the Senate and Electoral College toward small states least affected by these changes—may allow the party to offset for years the advantages that Democrats are reaping from “economic and demographic change.” The result could be a sustained standoff between a Republican political coalition centered on the smaller places that reflect what America has been and a Democratic party grounded in the economically preeminent large metros forging the nation’s future.

.

.

Ronald Brownstein is a senior editor at The Atlantic and a senior political analyst for CNN.

.